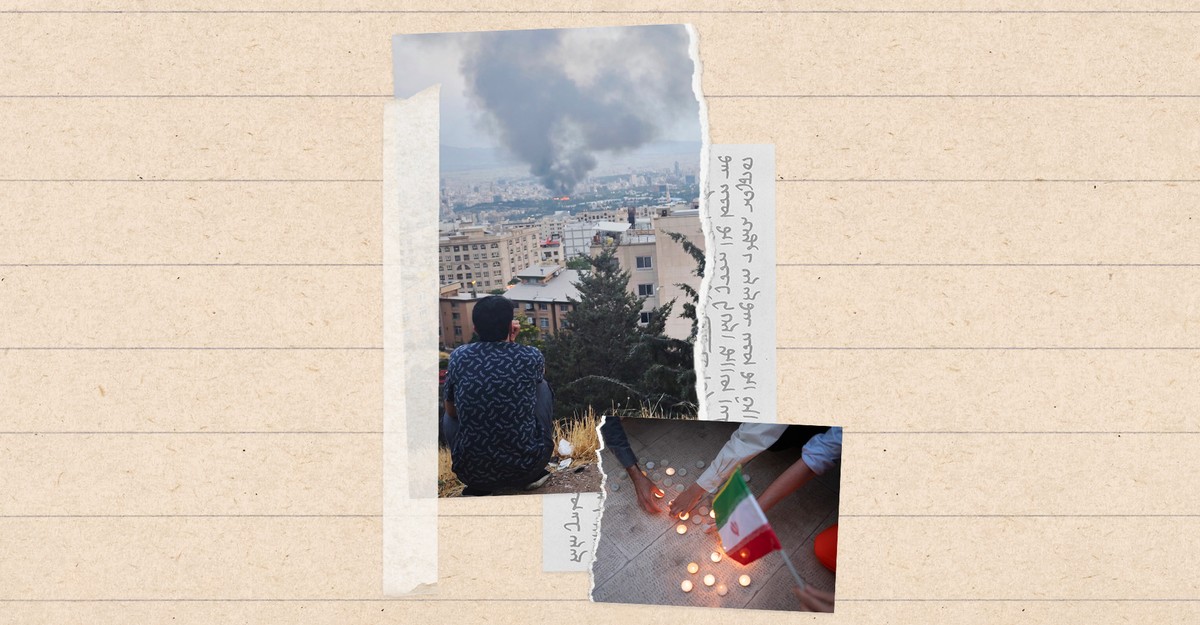

On June 13, 2025, Israel launched air strikes on nuclear and military sites in Iran. Over the 12 days that followed, the Israeli campaign expanded to include energy and other infrastructure; Iran retaliated with drone and missile strikes inside Israel; and the United States entered the conflict with strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities on June 22. Alireza Iranmehr is a novelist and an essayist who lives in the north of Iran but returned to Tehran to witness and document the bombardment. He sent the following series of short dispatches to his translator throughout the conflict.

2025年6月13日,以色列在伊朗的核和军事遗址上发动了空袭。在随后的12天内,以色列运动扩大到包括能源和其他基础设施。伊朗在以色列内部用无人机和导弹罢工进行报复;6月22日,美国因对伊朗核设施的罢工袭击。伊朗伊朗的阿里扎·伊朗(Alireza Iranmehr)是一位小说家和一位散文家,他住在伊朗北部,但返回德黑兰见证并记录轰炸。在整个冲突中,他将以下一系列简短派遣发送给了他的翻译。

J une 16, 8:30 p.m.

J UN 16,晚上8:30

The enormous roundabout at Azadi Square was full of cars, yet still felt somehow deserted. Then it dawned on me: Humans—they were mostly missing. Where normally tens of thousands of pedestrians thronged, now there were only a scattered few. Even many of the cars sat empty.

阿扎迪广场(Azadi Square)的巨大回旋处充满了汽车,但仍然感到荒芜。然后它突然出现在我身上:人类 - 他们大多失踪了。通常,数以万计的行人挤满了人,现在只有很少的行人。甚至许多汽车都空着。

Azadi Square is commonly the first place one sees upon arriving in Tehran and the last upon departure; several major expressways pass through it, and it is not far from Mehrabad Airport, which serves domestic flights. The airport reportedly had been bombarded a couple of days before, but I could not discern any sign of destruction from where I stood—just the smell of burned plastic cutting through the usual city smog.

阿扎迪广场(Azadi Square)通常是到达德黑兰(Tehran)时第一个看到的地方,而出发后最后一次看到。几个主要高速公路通过它,距离为国内航班的Mehrabad机场不远。据报道,该机场几天前曾被轰炸,但我无法辨别出我站立的任何破坏迹象,只是燃烧的塑料散发出通常的城市烟雾的气味。

Earlier that day, in Bandar Anzali, on the Caspian shore, I had been lucky to find a cab driver willing to bring me all the way to Tehran. The driver told me that he’d made the opposite trip with three young women in the middle of the night—and charged them 25 times the going rate. “You can see what’s going on,” he said. “There’s no gas. All the cars are stuck on the road. This is a five-hour trip, and it took us 15 hours.”

那天早些时候,在里海海岸的班达·安扎利(Bandar Anzali),我很幸运地找到了一个愿意把我带到德黑兰的出租车司机。司机告诉我,他在半夜与三名年轻女性进行了相反的旅行,并指控她们的25倍。他说:“你可以看到发生了什么。”“没有汽油。所有的汽车都被困在路上。这是一个五个小时的旅行,花了我们15个小时。”

He wasn’t lying: The stream of cars trying to get out of Tehran appeared endless. Some vehicles were stranded on the sides of the road, having run out of fuel. Men banded together to move huge concrete barriers out of the way, so that they could turn their vehicles around to head back into the city. My driver pointed to the rear of his car and said, “I had an extra four 20-gallon cans of gasoline just in case. I didn’t want to get stranded.”

他没有撒谎:试图离开德黑兰的汽车流似乎无尽。一些车辆被搁在道路的侧面,燃油用光了。男子团结起来,将巨大的混凝土屏障移开,以便他们可以将车辆转身回到城市。我的司机指着他的车后方说:“以防万一,我还有一个额外的四罐20加仑汽油。我不想被困。”

I asked why he didn’t just stay in Bandar Anzali after dropping off the women.

我问为什么他下车后不只是呆在班达·安扎利(Bandar Anzali)。

“And stay where? My wife and kids are back in Tehran,” he said. “And you? Why are you going to Tehran?”

他说:“待在哪里?我的妻子和孩子回到德黑兰。”“那你?你为什么要去德黑兰?”

I wanted to tell him that I was going back to Tehran to witness the most important event in Iran’s recent history, so that I could write about it. But that suddenly seemed ridiculous and unbelievable. I said instead, “I’m going to see some of my friends.”

我想告诉他,我要回到德黑兰,目睹伊朗最近历史上最重要的事件,以便我可以写信。但这突然看起来荒谬而令人难以置信。我说:“我要见一些我的朋友。”

He nodded. “Be careful,” he said, with a note of suspicion. “There are a lot of spies around these days in Tehran.”

他点点头。“要小心。”他怀疑说。“这些天在德黑兰周围有很多间谍。”

Was he suggesting that I might be one of those spies? It rubbed me the wrong way, but I didn’t say anything.

他是在暗示我可能是那些间谍之一吗?它以错误的方式摩擦了我,但我什么也没说。

Now, nearly alone in the middle of Azadi Square, I was seized with doubt, and then fear. The streets and sidewalks seemed wider than before, and newly ominous. I started to walk toward Azadi Boulevard when an ear-splitting sound threw me suddenly off balance.

现在,几乎一个人在阿扎迪广场(Azadi Square)中间,我怀疑被抓住,然后恐惧。街道和人行道似乎比以前更宽,而且新不祥。当耳塞的声音突然使我失去平衡时,我开始朝阿扎迪大道走去。

I looked up at the sky: Anti-aircraft fire and tracers appeared, clusters of little dots that ascended and then turned into flashes of white. There was nothing else in that sky. No airplanes. Down the road, I saw another man standing, looking up with intense curiosity, as though mesmerized.

我抬头看着天空:出现了防空火和示踪剂,一群小点升起,然后变成白色的闪光。那个天空中没有别的。没有飞机。在路上,我看到另一个男人站着,充满了好奇心,好像被迷住了。

A man watches the horizon from his roof in Tehran, June 16. (Atta Kenare / AFP / Getty)

一个男人在6月16日从他在德黑兰的屋顶上观看地平线。(Atta Kenare / AFP / Getty)

Read: The invisible city of Tehran

阅读:看不见的德黑兰市

No sirens sounded. No crowds ran looking for shelter. There was only the vacant expanse above, and an eerie noise like the buzzing of flies after the anti-aircraft guns went quiet. I’d heard somewhere that this was the sound of Israeli drones searching for their targets. Somewhere far away, an explosion boomed, and then came the anti-aircraft fire again, even farther away.

没有警报声。没有人群在寻找庇护所。上面只有空置的空缺,在防空枪变得安静之后,像苍蝇的嗡嗡声一样令人毛骨悚然。我在某处听说这是以色列无人机在寻找目标的声音。远处的某个地方,爆炸蓬勃发展,然后又来了防空大火,甚至更远。

Strange to say, but my fear lifted. I felt calm as I headed for the home of a friend on Jeyhoon Street—one who had decided to remain in Tehran and said I could spend the night. So I strolled, knowing the sky would light up again before long.

很奇怪,但是我的恐惧却取消了。当我前往Jeyhoon Street的一位朋友的家时,我感到很镇定。一个决定留在德黑兰,说我可以过夜。所以我漫步,知道天空会再次亮起。

J une 19

J A 19

At 2 a.m., after a long break, explosions came, one after another. I had left Jeyhoon Street and was now staying with Mostafa and Sahar, two of my best friends, in an apartment on the top floor of a building at the Ghasr Crossroad. This area of the city was packed with military and security sites that made likely targets for bombardment.

凌晨2点,漫长的休息后,爆炸又一次。我离开了Jeyhoon Street,现在与我最好的两个朋友Mostafa和Sahar住在Ghasr Crossroad建筑物顶层的公寓里。该市的这一地区充满了军事和安全遗址,可能是轰炸的目标。

Mostafa worked for the Tehran municipality. Sahar, after years of trying, was finally pregnant. When I’d called to ask if I could stay the night, they were delighted—at last, company in their anxiety. They’d remained in Tehran because Sahar had been prescribed strict bed rest.

Mostafa在德黑兰市工作。经过多年的尝试,萨哈尔终于怀孕了。当我打电话问我是否可以过夜时,他们很高兴 - 最后,他们焦虑不安。他们留在德黑兰,因为萨哈尔(Sahar)被处方了严格的床休息。

“If we stay, we may or may not get killed,” Mostafa told me. “But if we leave, our child will definitely not make it. So we’ve stayed.”

“如果我们留下来,我们可能会也可能不会被杀死,”莫斯塔法告诉我。“但是,如果我们离开,我们的孩子肯定不会做到。所以我们一直留下来。”

By 2:30 a.m., the sound of anti-aircraft fire was relentless. I saw a shadow moving in the hallway: Mostafa. He asked if I was awake, then made for my window, opening it. Now the sounds were exponentially louder, and a pungent odor of something burning entered the room. He’d come in here to smoke a cigarette, and in the effort to keep the smoke away from Sahar and their bedroom, he had allowed the entire apartment to be permeated by the scorching smell of war.

到凌晨2:30,防空大火的声音无情。我看到走廊上有一个阴影:Mostafa。他问我是否醒了,然后为我的窗户打开。现在,声音呈指数级,燃烧的东西进入房间的刺激性气味。他会来这里抽烟,为了使烟雾远离萨哈尔和他们的卧室,他允许整个公寓被炎热的战争气味渗透。

“Sahar isn’t afraid?” I asked him.

“萨哈尔不害怕吗?”我问他。

“Sahar is afraid of everything since the pregnancy,” he replied.

他回答:“萨哈尔(Sahar)害怕自怀孕以来的一切。”

A flash brightened the sky, and a few moments later, the sound of a distant blast swept over us. Mostafa left his half-smoked cigarette on the edge of the sill and hurried to check on Sahar. I saw a bright orange flame to the east of us outside. Apropos of nothing, or everything, I thought of “The Wall,” Jean-Paul Sartre’s short story set during the Spanish Civil War: Several prisoners huddle in a basement, waiting to be shot and wondering about the pain to come—whether it would be better to take a bullet to the face or to the gut. I imagined myself in the midst of that explosion, wondered whether shattered glass or falling steel beams and concrete would be what killed me.

闪光灯使天空照亮,片刻之后,遥远的爆炸声席卷了我们。莫斯塔法(Mostafa)将他的半烟的香烟留在了窗台的边缘,并急忙检查萨哈尔(Sahar)。我在我们外面的我们东部看到了一个明亮的橙色火焰。我想到的是“墙”,让·帕尔·萨特(Jean-Paul Sartre)在西班牙内战期间的短篇小说:几个囚犯挤在地下室里,等待被枪杀并想知道即将发生的痛苦,无论将子弹带到脸上或肠胃会更好。我以为自己在那次爆炸中,想知道碎裂的玻璃或掉落的钢梁和混凝土是否会杀死我。

Iran's air defense systems counter Israeli airstrikes in Tehran, June 21. (Hayi / Middle East Images / AFP / Getty)

伊朗的防空系统反以色列空袭,在德黑兰,6月21日。(Hayi / Middle East Images / AFP / Getty)

Mostafa reappeared. I asked how Sahar was doing.

Mostafa重新出现。我问萨哈尔表现如何。

“She’s still reading,” he said. “I think it was the Tehranpars district they just hit.”

他说:“她还在读书。”“我认为这是他们刚刚击中的德黑兰帕斯区。”

“No, it looked to me like it was Resalat,” I said. Then, after a pause: “You remember how during the war with Iraq, if anyone ever smoked in front of a window they’d say the guy is suicidal? For years, my father had blankets nailed over all our windows, to make sure our lights weren’t visible from outside.”

我说:“不,它看起来像是撒拉特。”然后,在暂停之后:“您还记得在与伊拉克战争期间,如果有人在窗户前抽烟,他们说这个家伙是自杀的?多年来,我父亲在我们所有的窗户上都钉了毯子,以确保我们的灯光从外面看不见。”

“They say the same thing now,” Mostafa said. “‘Don’t stand in front of windows.’ But I think it makes no difference. The more advanced technology gets, the less room you have to hide. Window or no window means nothing.”

“他们现在说同样的话,”莫斯塔法说。“‘不要站在窗户前。’但是我认为这没有什么区别。先进的技术得到的,您必须隐藏的空间越少。窗户或没有窗户没有任何意义。”

J une 20

J A 20

I’d imagined that getting inside Shariati Hospital without a press ID would be impossible. But as with just about everything else in Iran, access was a matter of having a contact.

我以为没有新闻ID就进入Shariati医院是不可能的。但是,与伊朗的几乎所有其他一切一样,访问是与联系的问题。

The hallways were packed with injured people, staff running every which way—more than one TV crew looked utterly lost on first entering the building. At one point, someone announced that the hospital was full and would have to redirect the newly injured elsewhere.

走廊上充满了受伤的人,工作人员各种各样的方式 - 超过一名电视工作人员在第一次进入建筑物时看上去完全失去了。有一次,有人宣布医院已经饱了,必须重定向新受伤的地方。

I stuck my head into rooms, as though looking for someone I’d lost. That was plausible enough under the circumstances that no one paid me any mind. After a while, I began to feel as though I really had lost somebody. The hospital had become a field of haphazard body parts, the smell of Betadine infusing everything.

我把头伸进房间,好像在寻找我失去的人。在没有人付出任何意见的情况下,这是足够合理的。过了一会儿,我开始感觉好像我真的失去了一个人。该医院已成为偶然的身体部位的领域,贝达丁的气味注入了一切。

A man sat quite still in the hallway, most of his face seemingly gone and wrapped in gauze. Another man had lost a hand. He stared quietly at the ceiling with a strangely beatific look, as though his face was made of clay that was now drying with the impression of an old smile that wouldn’t go away.

一个男人仍然坐在走廊上,他的大部分脸似乎都消失在纱布上。另一个男人失去了一只手。他用一个奇怪的脸色静静地凝视着天花板,好像他的脸是用粘土制成的,现在,他的粘土正在干燥,而旧的微笑的印象不会消失。

In one room, a TV crew interviewed a woman. She described the moment her home exploded. First, she’d heard multiple blasts in the distance. She told her husband and child to get away from the window. Then a flash, and the entire building trembled. Their apartment had been on the third floor, but when she opened her eyes, she was in the first-floor parking lot. Rescue workers still hadn’t found a trace of her husband or child. She began to cry, and I retreated back into the hallway, where an old man sat on his knees, praying. He was wearing a thick, black winter skullcap despite the heat. He looked up at me and said, “Half the house is gone. The other half remains. My son and daughter-in-law were in the other half.”

在一个房间里,电视工作人员采访了一个女人。她描述了她的房屋爆炸的那一刻。首先,她在远处听到了多次爆炸。她告诉丈夫和孩子,要离开窗户。然后闪烁,整个建筑物都发抖。他们的公寓位于三楼,但是当她睁开眼睛时,她在一楼的停车场。救援人员仍然没有找到她丈夫或孩子的痕迹。她开始哭泣,我退回到走廊,一个老人坐在膝盖上,祈祷。尽管炎热,他还是穿着厚实的黑色冬季头骨。他抬头看着我说:“一半的房子走了。另一半剩下。我的儿子和daughter妇在另一半。”

“Are they all right?” I asked him.

“他们好吗?”我问他。

The old man didn’t answer and went back to his praying. After a while, he started to weep. A half minute later came the sounds of air defenses. A woman screamed, pointing at the window, while several others tried to calm her down.

老人没有回答,回到他的祈祷。过了一会儿,他开始哭泣。半分钟后,防空声。一个女人尖叫,指着窗户,而其他几个人试图让她平静下来。

Outside, an ambulance wailed into the lot. Two days earlier, ambulances had been directed to turn off their sirens so as not to add to the general anxiety. But today, the alarms were back. I was in no special hurry to get to my next destination, but somehow I found myself speed-walking, even running, toward the address.

在外面,一辆救护车陷入了很多。两天前,救护车被指示关闭警笛,以免增加一般的焦虑。但是今天,警报又回来了。我并不是特别急于到达下一个目的地,但是以某种方式,我发现自己在地址上速度迅速,甚至跑步。

Arash Azizi: Iran’s stunning incompetence

Arash Azizi:伊朗令人惊叹的无能

The woman people had been calling the “cat lady” stood at her door, looking past me as though into a burning forest. I followed her to the kitchen, where she handed me a glass of lemonade. There had to be several dozen cats in that house—maybe 60 or more. The woman tiptoed among them like someone walking in a shallow pool of water. “Only 12 are mine,” she said. “The rest—their owners have been dropping off here the past few days.”

那个女人一直在称呼“猫夫人”的女人站在她的门口,看着我好像在燃烧的森林里。我跟着她去厨房,在那里她递给我一杯柠檬水。那所房子里必须有几十只猫 - 也许有60只或更多。那个女人像在浅水池中行走的人一样tip脚。她说:“只有12个是我的。”“其余的 - 他们的所有者在过去几天一直在这里下车。”

“How come they don’t fight with each other?” I asked. I’ve had my share of cats and know that they don’t readily share space with their own kind.

“他们怎么不互相战斗?”我问。我有很多猫,并且知道他们不容易与自己的种类共享空间。

She said, “In normal times, yes. They’d fight. But it’s as if they know what’s going on. When they first get here, they take one look around and then find a corner and sit quietly and wait.” During explosions, the cats would huddle together or hide under the furniture.

她说:“在正常的时期,是的。他们会打架。但这好像他们知道发生了什么。当他们第一次到达这里时,他们环顾四周,然后找到一个角落,安静地坐下来等待。”在爆炸期间,猫会挤在一起或躲在家具下。

I asked her whether she was also afraid. She smiled. “When you have to take care of this many cats, you don’t have time to be afraid.”

我问她是否也很害怕。她笑了。“当您必须照顾这么多猫时,您就没有时间害怕。”

A tabby with big, orange eyes rubbed against her ankles. She bent down to pick up the animal and caress it. Some people had abandoned their house pets on the streets when they left the city, she told me. They had little chance of surviving. She’d become the cat lady by posting an ad: For absolutely free, she was willing to take care of anyone’s cat.

一个大,橙色眼睛擦在她的脚踝上。她弯下腰捡起动物并爱抚它。她告诉我,当他们离开城市时,有些人在街上放弃了房屋宠物。他们几乎没有生存的机会。她通过发布广告来成为猫女士:绝对免费,她愿意照顾任何人的猫。

“My biggest problem right now is finding enough litter and dry food for them,” she told me. “All the pet shops are closed. I try to give them wet food that I cook myself. But a lot of them are not used to it and get diarrhea.”

她告诉我:“我现在最大的问题是为他们找到足够的垃圾和干粮。”“所有的宠物商店都关闭了。我试图给他们我自己做饭的湿食。但是很多人不习惯腹泻。”

She told me that one pet-shop owner she knew had promised to come back to Tehran that night with supplies. I contemplated that as I finished a second lemonade: A pet-shop owner returning to Tehran under bombardment to make sure these cats have litter and food.

她告诉我,她知道的一位宠物店老板当晚曾承诺将带着补给品回到德黑兰。我想到,当我完成第二件柠檬水时:一个宠物店老板在轰炸下返回德黑兰,以确保这些猫有垃圾和食物。

Back outside, the sky was quiet. Moving through the back alleys of the Yusefabad neighborhood, I found myself hurrying again, although I had no idea why.

回到外面,天空很安静。穿过Yusefabad社区的后排小巷,尽管我不知道为什么。

Tehran's Grand Bazaar, empty, on June 16 (Atta Kenare / AFP / Getty)

6月16日,德黑兰的大型集市(Atta Kenare / AFP / Getty)

J une 24

J A 24

A seemingly continuous flood of cars was returning to the city. Here and there, an anti-aircraft gun would go off for a second, but no one looked up at the sky anymore. Taxicabs were still rare and very expensive, but the metro and buses had been made free for everyone, at all hours.

看似连续的汽车洪水返回这座城市。在这里,一把防空枪会熄灭一秒钟,但没人抬头看着天空了。出租车仍然很罕见,而且非常昂贵,但是所有人都可以免费为所有人提供了公共汽车。

I decided to visit my publisher, Cheshmeh bookstore, on Karim Khan Avenue. My latest book came out just a month ago, but the war froze everything, book launches especially.

我决定拜访我的出版商Cheshmeh书店,位于Karim Khan Avenue上。我的最新书籍就在一个月前出现,但是战争冻结了一切,尤其是书籍。

Cheshmeh had hung a white banner outside. It read: Our shelter is the bookstore. The words gave me a warm feeling after days of fear. Inside, the store smelled of paper. Several of my old writer friends were there, amid a crowd talking about politics.

Cheshmeh在外面挂了一个白色的横幅。它阅读:我们的庇护所是书店。经过几天的恐惧,这些话给了我一种温暖的感觉。在里面,商店闻到了纸。我的几个老作家朋友在那里,在谈论政治的人群中。

A young man with tired eyes was showing his cellphone screen to two others and saying, “Look at what they’re writing about me. ‘He’s in the regime’s pay.’ Look at all these horrible emojis and comments. And why? Just because I posted something saying, ‘I pity our country and I’m against any foreigners attacking it.’”

一个疲惫的眼睛的年轻人向其他两个人展示了他的手机屏幕,并说:“看看他们在写关于我的东西。

“They write this sort of garbage about all of us,” a middle-aged man offered. “Don’t take it seriously. For all we know, they’re just pressure groups and bots.”

一名中年男子说:“他们写了这种垃圾。”“不要认真对待。我们所知道的,它们只是压力组和机器人。”

The young man didn’t want to hear it. “If I was in the pay of the government, don’t you think I should own a home by now at least? I’ve lost count of how many pages of my books they’ve censored over the years. Folk like us, we take beatings from both sides.”

年轻人不想听到它。“如果我掌握了政府的薪水,您不认为我至少应该拥有一个房子?我已经算出了他们多年来审查的书中有多少页。像我们一样,我们都从双方殴打。”

A gray-haired woman with a blue shawl over her shoulders said to him, “Do and say what you think is right, my son. Some people want to mix everything together.” She had a kindly voice that seemed to calm the young man down a little bit.

一个灰头发的女人在她的肩膀上戴着蓝色的披肩对他说:“我的儿子,做你认为是对的,有些人想把所有东西混合在一起。”她的声音似乎使年轻人平静下来。

From behind me, someone said, “I fear this cease-fire is a hoax.”

从我身后,有人说:“我担心这种停火是骗局。”

Another voice replied, “No, it’s really over. America entered to make sure they wrap it up.”

另一个声音回答:“不,它真的结束了。美国进入了确保它们包裹起来。”

I bought a newly translated book by a Korean author, chatted a little more with friends, and left, taking one last look at that miraculous white banner: Our shelter is our bookstore.

我买了一位韩国作家新翻译的书,与朋友聊了一点,然后最后看一下那个神奇的白色横幅:我们的庇护所是我们的书店。

I had hardly slept since the U.S. attack on Iran’s nuclear sites two days earlier. At my friend Nasser’s house, during the long night of explosions, I’d fixed my gaze on a small chandelier that never stopped quivering. The last night of the war was the absolute worst. A few hours after the world had announced an imminent cease-fire, Nasser’s windows were open. The familiar flash, the ensuing rattle and jolt. Nasser ran out of the kitchen with wet hands, shouting, “Didn’t the fools announce a cease-fire?”

自两天前美国袭击伊朗核网站以来,我几乎没有睡觉。在我的朋友纳赛尔(Nasser)的家中,在漫长的爆炸之夜,我将目光固定在一个从未停止颤抖的小枝形吊灯上。战争的最后一晚绝对是最糟糕的。在世界宣布即将停火的几个小时后,纳赛尔的窗户就开放了。熟悉的闪光,随之而来的嘎嘎声和震动。纳赛尔用湿手跑出厨房,大喊:“傻瓜不是宣布停火吗?”

The explosions came in seemingly endless waves. I was in the bathroom when one shook the building to what felt like the point of collapse. The lights went out, and there was a sound of shattering glass. I spotted Nasser in the living room. He was trying to stand up but couldn’t. That chandelier had finally broken into a hundred little pieces. Nasser said nothing, which was strange. I turned on my phone’s flashlight and shone it at him. He didn’t look right and kept his hand over the side of his abdomen. I turned the light to that area and saw blood.

爆炸似乎无尽的波浪。当一个人摇了摇建筑时,我当时在浴室里。灯熄灭了,玻璃碎了。我在客厅里发现纳赛尔。他试图站起来,但不能。那个吊灯终于分成了一百个小块。纳赛尔什么也没说,这很奇怪。我打开了手机的手电筒,向他发光。他看上去不正确,把手放在腹部的一侧。我把光转向那个区域,看到了鲜血。

“What happened?”

“发生了什么?”

“I have little pieces of glass inside me.”

“我里面有几块玻璃。”

“We have to go to the hospital.”

“我们必须去医院。”

“We can’t go now. Let’s go sit under the stairway. It’s safer there.”

“我们现在不能去。让我们坐在楼梯下。在那里更安全。”

Arash Azizi: A cease-fire without a conclusion

Arash Azizi:没有结论的停火

The building was empty. Everyone else seemed to have left the city. Nasser couldn’t: He was an electrical engineer for the national railway and had to remain at his post.

建筑物是空的。其他所有人似乎都离开了这座城市。纳赛尔不能:他是国家铁路的电气工程师,不得不留在他的职位上。

Under the stairs did not feel safer. The building was old and flimsy. I had the feeling that one more blast would send the whole thing crashing down on us. I examined Nasser’s wound under the flashlight. It was about eight inches long, but not very deep and not bleeding too much. I closed my eyes and tried to imagine that we were somewhere else when, from outside, I started to hear laughter and voices. I looked at Nasser to see whether I was imagining things. His face was chalk white, but he, too, had heard them.

在楼梯下,感觉不安全。这座建筑既旧又脆弱。我觉得又一次爆炸会使整个事情坠落在我们身上。我检查了纳赛尔在手电筒下的伤口。它长约八英寸,但不是很深,不会流血太多。我闭上眼睛,试图想象我们在其他地方,从外面开始听到笑声和声音。我看着纳赛尔看我是否在想象。他的脸是白色的,但他也听到了他们的声音。

I opened the door to the outside. Four teenagers were standing right there, in the middle of the street, watching the fireworks in the skies over Tehran with excitement. One of the boys was holding a huge sandwich, and the girls were decked out in the regalia of young goth and metal fans the world over. If it hadn’t been for the sound of explosions, I would have imagined I’d been thrown into another time and dimension altogether.

The kids looked thrilled to have run into us. One of the boys asked, “What’s happening, hajji?”

孩子们很高兴能遇到我们。其中一个男孩问:“发生了什么事,哈吉?”

“My friend’s been injured.”

“我的朋友受伤了。”

“Dangerous?”

“危险的?”

“I’m not sure. I’m thinking I should take him to a hospital.”

“我不确定。我认为我应该把他带到医院。”

“You need help?”

“你需要帮助吗?”

I backed Nasser’s car out of the garage. It was caked with dust and bits of chipped wall. The kids helped us, and two of them even volunteered to ride along to the hospital. The sounds of explosions retreated as we drove, but the silence that followed was deep and somehow foreboding.

我从车库里支持纳赛尔的汽车。它是用灰尘和碎墙的。孩子们帮助了我们,其中两个甚至自愿去医院。当我们开车时,爆炸的声音撤退了,但是随之而来的沉默却以某种方式预示着。

Nasser got stitched up fairly quickly. Dawn light was filtering into the emergency-room waiting area as we prepared to leave, people murmuring to one another that the cease-fire had begun. I looked around for the kids who’d come with us to the hospital. They were gone. I thought about how, years from now, they’d think back on that night, and I wondered how their memories would compare with Nasser’s and mine.

纳赛尔很快就被缝制了。当我们准备离开时,黎明灯正在急诊室等候区过滤,人们互相喃喃道,以免停火开始。我环顾四周,和我们一起去医院的孩子。他们走了。我想到了几年后,他们会在那天晚上回想一下,我想知道他们的记忆将如何与纳赛尔和我的记忆相提并论。

That was the last night. Now, leaving the bookstore, I went to the bus terminal at Azadi Square. Tehran was back in full swing; coming and going were easy too. I bought a ticket to Bandar Anzali and, as I boarded, took one last look at the Azadi Square monument—an elegant testimonial to the long suffering of modern Iran. The very next day, June 25, the Tehran Symphonic Orchestra was set to hold a free concert in the square. It was already hard to believe that this city had just experienced a war.

那是最后一个晚上。现在,离开书店,我去了阿扎迪广场的公交车站。德黑兰正如火如荼。来我也很容易。我买了一张班达·安扎利(Bandar Anzali)的票,当我登上登机票时,我最后一看阿扎迪广场纪念碑(Azadi Square Monument),这是现代伊朗长期苦难的优雅见证。第二天,6月25日,德黑兰交响乐团将在广场举行免费音乐会。已经很难相信这座城市刚刚经历了一场战争。

The monument at Azadi Square in Tehran, illuminated, on June 25. (Xinhua / Getty)

6月25日在德黑兰阿扎迪广场(Azadi Square)的纪念碑(新华社 /盖蒂)

*Photo-illustration by Jonelle Afurong / The Atlantic. Source: PATSTOCK / Getty; duncan1890 / Getty; fotograzia / Getty; natrot / Getty; Morteza Nikoubazl / NurPhoto / Getty; Getty.

*Jonelle Afurong / Atlantic的照片插图。资料来源:Patstock / Getty;Duncan1890 / Getty;Fotograzia / Getty;Natrot / Getty;Morteza Nikoubazl / Nurphoto / Getty;盖蒂。