This article was featured in the One Story to Read Today newsletter. Sign up for it here.

本文在一个故事中介绍了今天的新闻通讯。在这里注册。

I like to tell people that the night before I stopped sleeping, I slept. Not only that: I slept well. Years ago, a boyfriend of mine, even-keeled during the day but restless at night, told me how hard it was to toss and turn while I instantly sank into the crude, Neanderthal slumber of the dead. When I found a magazine job that allowed me to keep night-owl hours, my rhythms had the precision of an atomic clock. I fell asleep at 1 a.m. I woke up at 9 a.m. One to nine, one to nine, one to nine, night after night, day after day. As most researchers can tell you, this click track is essential to health outcomes: One needs consistent bedtimes and wake-up times. And I had them, naturally; when I lost my alarm clock, I didn’t bother getting another until I had an early-morning flight to catch.

我喜欢告诉人们,我停止睡觉的那天晚上,我睡了。不仅如此:我睡得很好。几年前,我的一个男朋友白天甚至在晚上都被不安,告诉我,当我立即陷入死者的粗俗,尼安德特人沉睡时,扔和转身有多困难。当我找到一份杂志工作,让我保留了夜猫子的时间时,我的节奏具有原子钟的精度。我在凌晨1点睡着了,我是在上午9点醒来的,一头一到九,一到九,一到九个晚上,一夜又一夜,一夜又一夜。正如大多数研究人员可以告诉您的那样,此点击轨道对于健康成果至关重要:一个人需要一致的床位和唤醒时间。我自然而然地有它们。当我失去闹钟时,直到我早上赶上飞行才能赶上。

Then, one night maybe two months before I turned 29, that vaguening sense that normal sleepers have when they’re lying in bed—their thoughts pixelating into surreal images, their mind listing toward unconsciousness—completely deserted me. How bizarre, I thought. I fell asleep at 5 a.m.

然后,大概在我29岁之前的两个月前,一个晚上,正常的卧铺躺在床上时,那种幻想的感觉 - 他们的想法像素化成超现实的图像,他们的思想融入了昏迷的脑海,使我抛弃了我。我以为多么奇怪。我在凌晨5点入睡

This started to happen pretty frequently. I had no clue why. The circumstances of my life, both personally and professionally, were no different from the week, month, or two months before—and my life was good. Yet I’d somehow transformed into an appliance without an off switch.

这开始经常发生。我不知道为什么。我个人和专业人生的情况与一周,一个月或两个月前都没有什么不同 - 我的生活很好。但是,我以某种方式将其转变为没有关闭开关的设备。

I saw an acupuncturist. I took Tylenol PM. I sampled a variety of supplements, including melatonin (not really appropriate, I’d later learn, especially in the megawatt doses Americans take—its real value is in resetting your circadian clock, not as a sedative). I ran four miles every day, did breathing exercises, listened to a meditation tape a friend gave me. Useless.

我看见了一个针灸师。我去了泰诺PM。我取样了各种补充剂,包括褪黑激素(不合适,以后我会学到,尤其是在美国人服用的兆瓦剂量中,它的真正价值在于重置您的昼夜节律时钟,而不是镇静剂)。我每天跑四英里,进行了呼吸练习,听了一个朋友给我的冥想录像带。无用。

I finally caved and saw my general practitioner, who prescribed Ambien, telling me to feel no shame if I needed it every now and then. But I did feel shame, lots of shame, and I’d always been phobic about drugs, including recreational ones. And now … a sedative? (Two words for you: Judy Garland.) It was only when I started enduring semiregular involuntary all-nighters—which I knew were all-nighters, because I got out of bed and sat upright through them, trying to read or watch TV—that I capitulated. I couldn’t continue to stumble brokenly through the world after nights of virtually no sleep.

我终于屈服了,看到我的全科医生,他们开了Ambien,告诉我如果时不时需要它,就不会感到羞耻。但是我确实感到羞耻,很羞耻,而且我一直对毒品(包括休闲毒品)感到恐惧。现在……镇静剂?(给您两个词:朱迪·加兰(Judy Garland)。)直到我开始忍受半智能的全夜,我知道这是全夜的人,因为我起床直立坐着他们,试图阅读或看电视,才能投降。几乎没有睡眠后,我无法继续在整个世界中偶然发现。

I hated Ambien. One of the dangers with this strange drug is that you may do freaky things at 4 a.m. without remembering, like making a stack of peanut-butter sandwiches and eating them. That didn’t happen to me (I don’t think?), but the drug made me squirrelly and tearful. I stopped taking it. My sleep went back to its usual syncopated disaster.

我讨厌Ambien。这种奇怪的药物的危险之一是,您可能会在凌晨4点做怪异的事情而不记住,例如制作一堆花生 - 巴特三明治并吃掉它们。那没有发生在我身上(我认为没有吗?),但是药物使我松鼠和眼泪。我停止服用了。我的睡眠回到了通常的综合灾难。

In Sleepless: A Memoir of Insomnia, Marie Darrieussecq lists the thinkers and artists who have pondered the brutality of sleeplessness, and they’re distinguished company: Duras, Gide, Pavese, Sontag, Plath, Dostoyevsky, Murakami, Borges, Kafka. (Especially Kafka, whom she calls literature’s “patron saint” of insomniacs. “Dread of night,” he wrote. “Dread of not-night.”) Not to mention F. Scott Fitzgerald, whose sleeplessness was triggered by a single night of warfare with a mosquito.

在《失眠:失眠症回忆录》中,玛丽·达里乌斯(Marie Darrieussecq)列出了思考的思想家和艺术家,这些思想家和艺术家都在思考失眠的残酷性,它们是杰出的公司:杜拉斯(Duras),吉德(Gide),帕维斯(Gide),帕维斯(Pavese),普拉斯(Sontag),普拉斯(Sontag),普拉斯(Sontag),普拉斯(Sontag),多斯托耶夫斯基(Dostoyevsky),杜斯托耶夫斯基(Dostoyevsky),穆拉卡米(Murakami),穆拉卡米(Murakami),伯格斯(Murakami,Borges),卡夫卡(Kafka)。(尤其是卡夫卡(Kafka),她称其为文学的“失眠症的守护神”。“夜晚的恐惧。”他写道。“恐惧的夜晚。”)更不用说F. Scott Fitzgerald,他的失眠是由一夜的战争触发的。

But there was sadly no way to interpret my sleeplessness as a nocturnal manifestation of tortured genius or artistic brilliance. It felt as though I’d been poisoned. It was that arbitrary, that abrupt. When my insomnia started, the experience wasn’t just context-free; it was content-free. People would ask what I was thinking while lying wide awake at 4 a.m., and my answer was: nothing. My mind whistled like a conch shell.

但是可悲的是,没有办法将我的失眠解释为折磨天才或艺术才华的夜间体现。感觉好像我被毒了。就是这样,突然的。当我的失眠开始时,体验不仅是无上下文的。这是没有内容的。人们会问我在凌晨4点醒着时在想什么,我的回答是:什么都没有。我的思想像海螺外壳一样吹口哨。

But over time I did start thinking—or worrying, I should say, and then perseverating, and then outright panicking. At first, songs would whip through my head, and I couldn’t get the orchestra to pack up and go home. Then I started to fear the evening, going to bed too early in order to give myself extra runway to zonk out. (This, I now know, is a typical amateur’s move and a horrible idea, because the bed transforms from a zone of security into a zone of torment, and anyway, that’s not how the circadian clock works.) Now I would have conscious thoughts when I couldn’t fall asleep, which can basically be summarized as insomnia math: Why am I not falling asleep Dear God let me fall asleep Oh my God I only have four hours left to fall asleep oh my God now I only have three oh my God now two oh my God now just one.

但是随着时间的流逝,我确实开始思考 - 或者担心,然后坚持不懈,然后完全惊慌。起初,歌曲会在我的脑海中鞭打,而我无法让乐团收拾好回家。然后,我开始担心晚上,为了给自己额外的跑道去Zonk出来。(This, I now know, is a typical amateur’s move and a horrible idea, because the bed transforms from a zone of security into a zone of torment, and anyway, that’s not how the circadian clock works.) Now I would have conscious thoughts when I couldn’t fall asleep, which can basically be summarized as insomnia math: Why am I not falling asleep Dear God let me fall asleep Oh my God I only have four hours left to fall asleep oh my God now我现在只有三个哦,我的上帝,两个哦,我的上帝现在只有一个。

“The insomniac is not so much in dialogue with sleep,” Darrieussecq writes, “as with the apocalypse.”

达里乌斯克(Darrieussecq)写道:“失眠与睡眠对话并不是很多,就像启示录一样。”

I would shortly discover that this cycle was textbook insomnia perdition: a fear of sleep loss that itself causes sleep loss that in turn generates an even greater fear of sleep loss that in turn generates even more sleep loss … until the next thing you know, you’re in an insomnia galaxy spiral, with a dark behavioral and psychological (and sometimes neurobiological) life of its own.

我很快会发现,这个周期是教科书失眠的灭亡:对睡眠损失的恐惧本身会导致睡眠损失,从而使对睡眠损失的恐惧更加恐惧,从而导致更多的睡眠损失……直到您知道下一件事,您知道您是一个失眠的银河系螺旋,具有黑暗的行为和心理学(有时是神经生物学)的生命。

I couldn’t recapture my nights. Something that once came so naturally now seemed as impossible as flying. How on earth could this have happened? To this day, whenever I think about it, I still can’t believe it did.

我无法恢复我的夜晚。曾经自然而然地出现的东西似乎像飞行一样不可能。到底是怎么发生的?直到今天,每当我考虑它时,我仍然不敢相信它确实如此。

In light of my tortured history with the subject, you can perhaps see why I generally loathe stories about sleep. What they’re usually about is the dangers of sleep loss, not sleep itself, and as a now-inveterate insomniac, I’ve already got a multivolume fright compendium in my head of all the terrible things that can happen when sleep eludes you or you elude it. You will die of a heart attack or a stroke. You will become cognitively compromised and possibly dement. Your weight will climb, your mood will collapse, the ramparts of your immune system will crumble. If you rely on medication for relief, you’re doing your disorder all wrong—you’re getting the wrong kind of sleep, an unnatural sleep, and addiction surely awaits; heaven help you and that horse of Xanax you rode in on.

鉴于我对这个主题的折磨历史,您也许可以理解为什么我通常讨厌关于睡眠的故事。他们通常是睡眠损失的危险,而不是睡眠本身,而作为现在的入侵失眠症,我已经在我的脑海中有一个多卷恐怖的纲要,因为当睡眠躲避或您躲避时,所有可怕的事情可能会发生。您将死于心脏病或中风。您将被认知妥协,甚至可能是痴呆症。您的体重将攀升,心情会崩溃,免疫系统的城墙会崩溃。如果您依靠药物来缓解药物,那么您的疾病都错了 - 您的睡眠不正确,睡眠不自然和成瘾肯定会等待;天堂帮助您和您骑的Xanax马。

It should go without saying that for some of us, knowledge is not power. It’s just more kindling.

不用说对于我们中的某些人来说,知识不是力量。这只是点燃。

The cultural discussions around sleep would be a lot easier if the tone weren’t quite so hectoring—or so smug. A case in point: In 2019, the neuroscientist Matthew Walker, the author of Why We Sleep, gave a TED Talk that began with a cheerful disquisition about testicles. They are, apparently, “significantly smaller” in men who sleep five hours a night rather than seven or more, and that two-hour difference means lower testosterone levels too, equivalent to those of someone 10 years their senior. The consequences of short sleep for women’s reproductive systems are similarly dire.

如果语气不太喜欢或自鸣得意,那么关于睡眠的文化讨论会容易得多。一个恰当的例子:2019年,神经科学家马修·沃克(Matthew Walker)是为什么我们睡觉的作者,他进行了一场TED演讲,始于对睾丸的开朗摘要。显然,他们每晚睡觉五个小时而不是七个或更高的男性“显然要小得多”,而两个小时的差异也意味着较低的睾丸激素水平,相当于十年的大四学生。女性生殖系统短睡眠的后果同样可怕。

“This,” Walker says just 54 seconds in, “is the best news that I have for you today.”

沃克说:“这是我今天为您提供的最好的消息。”

He makes good on his promise. What follows is the old medley of familiars, with added verses about inflammation, suicide, cancer. Walker’s sole recommendation at the end of his sermon is the catechism that so many insomniacs—or casual media consumers, for that matter—can recite: Sleep in a cool room, keep your bedtimes and wake-up times regular, avoid alcohol and caffeine. Also, don’t nap.

他兑现了诺言。接下来是熟悉的老混蛋,并增加了有关炎症,自杀,癌症的经文。讲道结束时沃克的唯一建议是教理主义,以至于许多失眠症(或随意的媒体消费者)可以背诵:在凉爽的房间里睡觉,保持睡眠时间和唤醒时间,避免使用酒精和咖啡因。另外,不要小睡。

I will now say about Walker:

我现在会说沃克:

1. His book is in many ways quite wonderful—erudite and wide-ranging and written with a flaring energy when it isn’t excessively pleased with itself.

1。他的书在许多方面都非常出色 - 横向和广泛,并以耀眼的能量对自己感到过分满意。

2. Both Why We Sleep and Walker’s TED Talk focus on sleep deprivation, not insomnia, with the implicit and sometimes explicit assumption that too many people choose to blow off sleep in favor of work or life’s various seductions.

2。为什么我们睡觉和沃克的TED谈话重点是睡眠剥夺,而不是失眠,有时甚至是明确的假设,即太多的人选择吹睡眠,而不是工作或生活的各种诱惑。

If public awareness is Walker’s goal (certainly a virtuous one), he and his fellow researchers have done a very good job in recent years, with the enthusiastic assistance of my media colleagues, who clearly find stories about the hazards of sleep deprivation irresistible. (In the wine-dark sea of internet content, they’re click sirens.) Walker’s TED Talk has been viewed nearly 24 million times. “For years, we were fighting against ‘I’ll sleep when I’m dead,’ ” Aric Prather, the director of the behavioral-sleep-medicine research program at UC San Francisco, told me. “Now the messaging that sleep is a fundamental pillar of human health has really sunk in.”

如果公众意识是沃克的目标(肯定是一个贤惠的目标),那么近年来,他和他的研究人员在我的媒体同事的热情协助下做得很好,他们清楚地发现了有关睡眠剥夺危害的故事。(在互联网含量的葡萄酒黑暗海洋中,它们是单击警报器。)沃克的TED演讲已被观看了近2400万次。“多年来,我们一直在与'我死后睡觉’的斗争。”加州大学旧金山加州大学旧金山行为 - 睡眠医学研究计划的主任阿里克·普拉瑟(Aric Prather)告诉我。“现在,睡眠是人类健康的基本支柱的消息确实已经沉入。”

Yet greater awareness of sleep deprivation’s consequences hasn’t translated into a better-rested populace. Data from the CDC show that the proportion of Americans reporting insufficient sleep held constant from 2013 through 2022, at roughly 35 percent. (From 2020 to 2022, as anxiety about the pandemic eased, the percentage actually climbed.)

然而,对睡眠剥夺后果的意识更高并没有转化为更好的民众。CDC的数据表明,从2013年到2022年,美国人报告睡眠不足的比例不变,约为35%。(从2020年到2022年,随着对大流行的焦虑,实际上的百分比实际上攀升了。)

So here’s the first question I have: In 2025, exactly how much of our “sleep opportunity,” as the experts call it, is under our control?

因此,这是我第一个问题:2025年,正如专家所说的那样,我们的“睡眠机会”到底是多少?

According to the most recent government data, 16.4 percent of American employees work nonstandard hours. (Their health suffers in every category—the World Health Organization now describes night-shift work as “probably carcinogenic.”) Adolescents live in a perpetual smog of sleep deprivation because they’re forced to rise far too early for school (researchers call their plight “social jet lag”); young mothers and fathers live in a smog of sleep deprivation because they’re forced to rise far too early (or erratically) for their kids; adults caring for aging parents lose sleep too. The chronically ill frequently can’t sleep. Same with some who suffer from mental illness, and many veterans, and many active-duty military members, and menopausal women, and perimenopausal women, and the elderly, the precariat, the poor.

根据最近的政府数据,有16.4%的美国雇员工作时间不算时间。(他们的健康遭受了每个类别的遭受的痛苦 - 世界卫生组织现在将夜班工作描述为“可能的致癌”。)青少年生活在一个永久的睡眠剥夺烟雾中,因为他们被迫过早地升起学校(研究人员称他们的困境“社会喷气滞后”);年轻的母亲和父亲生活在睡眠不足的烟雾中,因为他们被迫为孩子们崛起(或不规律的)。照顾老龄父母的成年人也失去睡眠。慢性病经常无法入睡。与一些患有精神疾病的人,许多退伍军人,许多现役军人,绝经妇女,围裙妇女,以及老年人,prect省,穷人。

“Sleep opportunity is not evenly distributed across the population,” Prather noted, and he suspects that this contributes to health disparities by class. In 2020, the National Center for Health Statistics found that the poorer Americans were, the greater their likelihood of reporting difficulty falling asleep. If you look at the CDC map of the United States’ most sleep-deprived communities, you’ll see that they loop straight through the Southeast and Appalachia. Black and Hispanic Americans also consistently report sleeping less, especially Black women.

Prather指出:“睡眠机会不会均匀分布在整个人群中,”他怀疑这会导致班级健康差异。2020年,国家卫生统计中心发现,较贫穷的美国人是他们报告难以入睡的可能性越大。如果您查看美国最睡眠不足的社区的CDC地图,您会发现它们直接穿过东南和阿巴拉契亚。黑人和西班牙裔美国人也始终报告睡眠较少,尤其是黑人妇女。

Even for people who aren’t contending with certain immutables, the cadences of modern life have proved inimical to sleep. Widespread electrification laid waste to our circadian rhythms 100 years ago, when they lost any basic correspondence with the sun; now, compounding matters, we’re contending with the currents of a wired world. For white-collar professionals, it’s hard to imagine a job without the woodpecker incursions of email or weekend and late-night work. It’s hard to imagine news consumption, or even ordinary communication, without the overstimulating use of phones and computers. It’s hard to imagine children eschewing social media when it’s how so many of them socialize, often into the night, which means blue-light exposure, which means the suppression of melatonin. (Melatonin suppression obviously applies to adults too—it’s hardly like we’re avatars of discipline when it comes to screen time in bed.)

即使对于那些不与某些不变的人竞争的人,现代生活的节奏也被证明是不利的。100年前,当他们失去与太阳的任何基本通信时,广泛的电气化浪费了我们的昼夜节律;现在,复杂的问题,我们正在与有线世界的潮流竞争。对于白领专业人士来说,很难想象没有啄木鸟的啄木鸟或周末和深夜工作的工作。很难想象新闻消费,甚至是普通的沟通,而不会过度刺激手机和计算机。很难想象孩子们避开社交媒体时,当他们有这么多的社交经常到夜间社交时,这意味着蓝光的暴露,这意味着抑制褪黑激素。(褪黑激素抑制显然也适用于成年人 - 这几乎不像我们在床上放映时间时是纪律的化身。)

Most of us can certainly do more to improve or reclaim our sleep. But behavioral change is difficult, as anyone who’s vowed to lose weight can attest. And when the conversation around sleep shifts the onus to the individual—which, let’s face it, is the American way (we shift the burden of child care to the individual, we shift the burden of health care to the individual)—we sidestep the fact that the public and private sectors alike are barely doing a thing to address what is essentially a national health emergency.

我们大多数人当然可以做更多的事情来改善或恢复我们的睡眠。但是,行为改变很困难,因为任何誓言减肥的人都可以证明。当围绕睡眠的谈话将责任转移到个人时(面对现实,这就是美国的方式(我们将托儿的负担转移到个人身上,我们将卫生保健负担转移到个人身上),我们避开了公共和私营部门几乎没有做一些事情来解决本质上是国家健康紧急情况的事实。

Given that we’ve decided that an adequate night’s rest is a matter of individual will, I now have a second question: How are we to discuss those who are suffering not just from inadequate sleep, but from something far more severe? Are we to lecture them in the same menacing, moralizing way? If the burden of getting enough sleep is on us, should we consider chronic insomniacs—for whom sleep is a nightly gladiatorial struggle—the biggest failures in the armies of the underslept?

鉴于我们已经确定一个足够的夜晚休息是个人意志的问题,所以我现在有一个问题:我们如何讨论那些不仅因睡眠不足而受苦而受苦的人,而且要与更严重的事情讨论?我们是否以同样的险恶,道德的方式演讲?如果我们有足够的睡眠负担,我们是否应该考虑慢性失眠症(对于谁是每晚的角斗斗争),这是底面级船员军队中最大的失败?

Those who can’t sleep suffer a great deal more than those gifted with sleep will ever know. Yet insomniacs frequently feel shame about the solutions they’ve sought for relief—namely, medication—likely because they can detect a subtle, judgmental undertone about this decision, even from their loved ones. Resorting to drugs means they are lazy, refusing to do simple things that might ease their passage into unconsciousness. It means they are neurotic, requiring pills to transport them into a natural state that every other animal on Earth finds without aid.

那些无法入睡的人比那些有天赋的睡眠的人会知道。然而,失眠症经常对他们寻求缓解的解决方案(即药物)感到羞耻,这很可能是因为他们可以发现对这一决定,甚至是亲人的判断力。诉诸毒品意味着他们很懒惰,拒绝做一些简单的事情,这些事情可能会减轻他们的失去意识。这意味着它们是神经质的,需要药丸将它们运输到天然状态,地球上其他动物在没有援助的情况下找到。

Might I suggest that these views are unenlightened? “In some respects, chronic insomnia is similar to where depression was in the past. We’d say, ‘Major depression’ and people would say, ‘Everybody gets down now and then,’ ” John Winkelman, a psychiatrist in the sleep-medicine division at Harvard Medical School, said at a panel I attended last summer. Darrieussecq, the author of Sleepless, puts it more bluntly: “ ‘I didn’t sleep all night,’ sleepers say to insomniacs, who feel like replying that they haven’t slept all their life.”

我可能会建议这些观点没有得到启示?“在某些方面,慢性失眠与过去的抑郁症相似。我们会说,'严重抑郁',人们会说,'每个人时不时地倒下,’”哈佛医学院睡眠医学院的精神病医生约翰·温克尔曼(John Winkelman)在去年夏天参加的一个小组成员。失眠的作者Darrieussecq更直截了当地说:“‘我没有整夜睡觉,'sleepers对Insomniacs说,他们想回答他们一生都没有睡过。”

The fact is, at least 12 percent of the U.S. population suffers from insomnia as an obdurate condition. Among Millennials, the number pops up to 15 percent. And 30 to 35 percent of Americans suffer from some of insomnia’s various symptoms—trouble falling asleep, trouble staying asleep, or waking too early—at least temporarily. In 2024, there were more than 2,500 sleep-disorder centers in the U.S. accredited by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Prather told me the wait time to get into his sleep clinic at UCSF is currently a year. “That’s better than it used to be,” he added. “Until a few months ago, our waitlist was closed. We couldn’t fathom giving someone a date.”

事实是,至少12%的美国人口遭受失眠状态。在千禧一代中,这个数字高达15%。至少至少暂时暂时,有30%至35%的美国人患有失眠症的某些症状(陷入困境,入睡或过早醒来)。2024年,美国睡眠医学学院认可的美国有超过2500个睡眠状态中心。普拉瑟(Prather)告诉我,在UCSF的睡眠诊所的等待时间目前为一年。他补充说:“这比以前更好。”“直到几个月前,我们的候补名单才关闭。我们无法理解给某人约会。”

So what I’m hoping to do here is not write yet another reproachful story about sleep, plump with misunderstandings and myths. Fixing sleep—obtaining sleep—is a tricky business. The work it involves and painful choices it entails deserve nuanced examination. Contrary to what you might have read, our dreams are seldom in black and white.

因此,我希望在这里做的事情不是写另一个关于睡眠,充满误解和神话的责备的故事。修复睡眠(振奋睡眠)是一项棘手的生意。它涉及的工作和痛苦的选择需要进行细微的检查。与您可能阅读的内容相反,我们的梦想很少是黑白的。

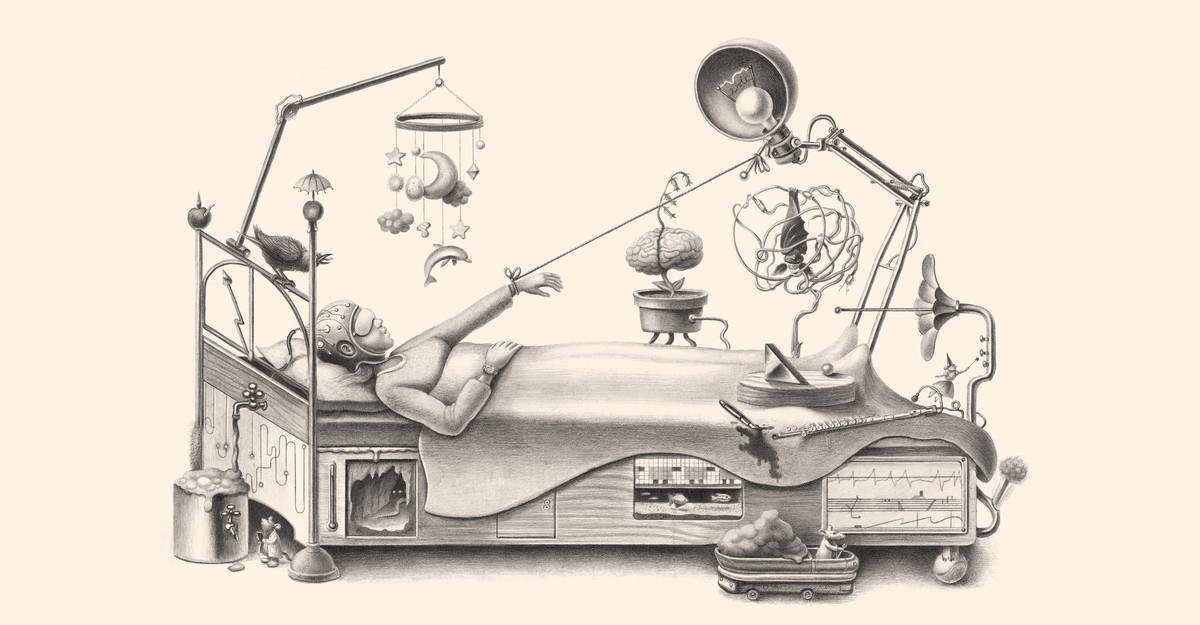

Armando Veve

Armando Veve

Whenever I interviewed a clinician, psychiatrist, neuroscientist, or any other kind of expert for this story, I almost always opened with the same question: What dogma about sleep do you think most deserves to be questioned?

每当我采访临床医生,精神科医生,神经科学家或任何其他类型的专家时,我几乎总是以同样的问题开放:您认为大多数关于睡眠的教条应该受到质疑?

The most frequent answer, by a long chalk, is that we need eight hours of it. A fair number of studies, it turns out, show that mortality rates are lowest if a person gets roughly seven hours. Daniel F. Kripke, a psychiatrist at UC San Diego, published the most famous of these analyses in 2002, parsing a sample of 1.1 million individuals and concluding that those who reported more than eight hours of sleep a night experienced significantly increased mortality rates. According to Kripke’s work, the optimal sleep range was a mere 6.5 to 7.4 hours.

长长的粉笔最常见的答案是我们需要八个小时的时间。事实证明,很多研究表明,如果一个人大约有七个小时,死亡率最低。加州大学圣地亚哥分校的精神科医生丹尼尔·F·克里普克(Daniel F.根据Kripke的工作,最佳睡眠范围仅为6.5至7.4小时。

These numbers shouldn’t be taken as gospel. The relationship between sleep duration and health outcomes is a devil’s knot, though Kripke did his best to control for the usual confounds—age, sex, body-mass index. But he could not control for the factors he did not know. Perhaps many of the individuals who slept eight hours or more were doing so because they had an undetected illness, or an illness of greater severity than they’d realized, or other conditions Kripke hadn’t accounted for. The study was also observational, not randomized.

这些数字不应被视为福音。睡眠持续时间与健康成果之间的关系是魔鬼的结,尽管克里普克(Kripke)竭尽全力控制通常的混杂 - 年龄,性别,身体质量索引。但是他无法控制他不知道的因素。也许睡过八个小时或更长时间的许多人之所以这样做,是因为他们患有未发现的疾病,或者患有比他们意识到的更严重的疾病,或者克里普克(Kripke)没有考虑到其他情况。该研究也是观察性的,而不是随机的。

But even if they don’t buy Kripke’s data, sleep experts don’t necessarily believe that eight hours of sleep has some kind of mystical significance. Methodologically speaking, it’s hard to determine how much sleep, on average, best suits us, and let’s not forget the obvious: Sleep needs—and abilities—vary over the course of a lifetime, and from individual to individual. (There’s even an extremely rare species of people, known as “natural short sleepers,” associated with a handful of genes, who require only four to six hours a night. They tear through the world as if fired from a cannon.) Yet eight hours of sleep or else remains one of our culture’s most stubborn shibboleths, and an utter tyranny for many adults, particularly older ones.

但是,即使他们不购买Kripke的数据,睡眠专家也不一定相信八个小时的睡眠具有某种神秘意义。从方法论上讲,很难平均确定多少睡眠,最适合我们,并且不要忘记明显的:睡眠需求和能力在一生中,从个人到个人。(甚至还有一种非常稀有的人,被称为“天然短卧铺”,与少数基因相关,他们每晚只需要四到六个小时。他们像从大炮上开火一样撕裂。)却八个小时的睡眠或否则仍然是我们文化最顽固的shibboleths之一,对许多成年人(尤其是老年人)来说是一个完全的暴政。

“We have people coming into our insomnia clinic saying ‘I’m not sleeping eight hours’ when they’re 70 years of age,” Michael R. Irwin, a psychoneurologist at UCLA, told me. “And the average sleep in that population is less than seven hours. They attribute all kinds of things to an absence of sleep—decrements in cognitive performance and vitality, higher levels of fatigue—when often that’s not the case. I mean, people get older, and the drive to sleep decreases as people age.”

加州大学洛杉矶分校(UCLA)的心理学家迈克尔·R·欧文(Michael R. Irwin)告诉我:“我们有人进入失眠症诊所,说'我不睡八个小时'。”“人群中的平均睡眠不到七个小时。它们将各种事情归因于没有睡眠的情况 - 认知表现和活力的责任,疲劳水平较高,但事实并非如此。我的意思是,人们年龄较大,并且随着人们的年龄增长,睡眠的动力降低了。”

Another declaration I was delighted to hear: The tips one commonly reads to get better sleep are as insipid as they sound. “Making sure that your bedroom is cool and comfortable, your bed is soft, you have a new mattress and a nice pillow—it’s unusual that those things are really the culprit,” Eric Nofzinger, the former director of the sleep neuroimaging program at the University of Pittsburgh’s medical school, told me. “Most people self-regulate anyway. If they’re cold, they put on an extra blanket. If they’re too warm, they throw off the blanket.”

我很高兴听到的另一项声明是:人们通常会读到更好的睡眠的技巧,就像听起来一样平淡。匹兹堡大学医学院的睡眠神经影像计划前校长埃里克·诺辛格(Eric Nofzinger)告诉我:“确保您的卧室凉爽舒适,床很柔软,您的床很柔软,您有一个新的床垫和一个漂亮的枕头,这确实是罪魁祸首。”“无论如何,大多数人都会自我调节。如果他们很冷,他们会戴上额外的毯子。如果太热了,他们就会掉下毯子。”

“Truthfully, there’s not a lot of data supporting those tips,” Suzanne Bertisch, a behavioral-sleep-medicine expert at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, in Boston, told me. That includes the proscription on naps, she added, quite commonly issued in her world. (In general, the research on naps suggests that short ones have beneficial outcomes and long ones have negative outcomes, but as always, cause and effect are difficult to disentangle: An underlying health condition could be driving those long naps.)

“说实话,没有太多支持这些技巧的数据,”波士顿Brigham and妇女医院的行为脚步医学专家Suzanne Bertisch告诉我。她补充说,这包括在她的世界上通常发行的小睡。(总的来说,对小睡的研究表明,短期的结果具有有益的结果,并且长期的结果具有负面结果,但是一如既往,因果关系很难解散:潜在的健康状况可能会驱动那些长时间的小睡。)

Even when they weren’t deliberately debunking the conventional wisdom about sleep, many of the scholars I spoke with mentioned—sometimes practically as an aside—facts that surprised or calmed. For instance: Many of us night owls have heard that the weather forecast for our old age is … well, cloudy, to be honest, with a late-afternoon chance of keeling over. According to one large analysis, we have a 10 percent increase in all-cause mortality over morning larks. But Jeanne Duffy, a neuroscientist distinguished for her expertise in human circadian rhythms at Brigham and Women’s, told me she suspected that this was mainly because most night owls, like most people, are obliged to rise early for their job.

即使他们没有故意揭穿有关睡眠的传统智慧,我与之交谈的许多学者(有时实际上是旁边)使人感到惊讶或平静。例如:我们中的许多夜猫子都听说我们老年的天气预报是……嗯,多云,老实说,午后有机会屈服。根据一项大分析,我们的全因死亡率比早晨的百灵鸟增加了10%。但是,珍妮·达菲(Jeanne Duffy)是一位因在杨百翰(Brigham)和女性人类昼夜节律方面的专业知识而杰出的神经科学家,她告诉我她怀疑这主要是因为大多数夜猫子(像大多数人一样,大多数夜猫子都必须早起,都必须早起。

So wait, I said. Was she implying that if night owls could contrive work-arounds to suit their biological inclination to go to bed late, the news probably wouldn’t be as grim?

所以等等,我说。她是否暗示,如果夜猫子可以构成工作能力以适合他们的生物学倾向来上床睡觉,那么这个消息可能不会那么严峻?

“Yes,” she replied.

“是的,”她回答。

A subsequent study showed that the owl-lark mortality differential dwindled to nil when the authors controlled for lifestyle. Apparently owls are more apt to smoke, and to drink more. So if you’re an owl who’s repelled by Marlboros and Jameson, you’re fine.

随后的一项研究表明,当作者控制生活方式时,猫头鹰的死亡率差异逐渐减少。显然,猫头鹰更容易抽烟,喝更多。因此,如果您是马尔伯罗斯(Marlboros)和詹姆森(Jameson)击退的猫头鹰,那就很好。

Kelly Glazer Baron, the director of the behavioral-sleep-medicine program at the University of Utah, told me that she’d love it if patients stopped agonizing over the length of their individual sleep phases. I didn’t get enough deep sleep, they fret, thrusting their Apple Watch at her. I didn’t get enough REM. And yes, she said, insufficiencies in REM or slow-wave sleep can be a problem, especially if they reflect an underlying health issue. But clinics don’t look solely at sleep architecture when evaluating their patients.

犹他大学行为脚步医学计划的主任凯利·格拉泽·男爵(Kelly Glazer Baron)告诉我,如果患者停止在各个睡眠阶段的长度上感到痛苦,她会喜欢它。我没有足够的深度睡眠,他们烦恼,向她伸出苹果手表。我没有得到足够的REM。她说,是的,REM或慢波睡眠的不足可能是一个问题,尤其是当它们反映了潜在的健康问题时。但是,在评估患者时,诊所并不仅仅看着睡眠结构。

“I often will show them my own data,” Baron said. “It always shows I don’t have that much deep sleep, which I find so weird, because I’m a healthy middle-aged woman.” In 2017, after observing these anxieties for years, Baron coined a term for sleep neuroticism brought about by wearables: orthosomnia.

“我经常会向他们展示自己的数据,”男爵说。“这总是表明我没有那么深的睡眠,因为我是一个健康的中年女人,所以我觉得很奇怪。”2017年,在观察到这些焦虑多年之后,男爵创造了一个由可穿戴设备带来的睡眠神经质的术语:Orthosomnia。

But most surprising—to me, anyway—was what I heard about insomnia and the black dog. “There are far more studies indicating that insomnia causes depression than depression causes insomnia,” said Wilfred Pigeon, the director of the Sleep & Neurophysiology Research Laboratory at the University of Rochester. Which is not to say, he added, that depression can’t or doesn’t cause insomnia. These forces, in the parlance of health professionals, tend to be “bidirectional.”

但是,无论如何,最令人惊讶的是,我对失眠和黑狗听说过。罗切斯特大学睡眠与神经生理学研究实验室主任Wilfred Pigeon说:“更多的研究表明失眠比抑郁会导致失眠。”他补充说,这并不是说抑郁症不会或不会引起失眠。根据卫生专业人员的说法,这些力量往往是“双向的”。

But I can’t tell you how vindicating I found the idea that perhaps my own insomnia came first. A couple of years into my struggles with sleeplessness, a brilliant psychopharmacologist told me that my new condition had to be an episode of depression in disguise. And part of me thought, Sure, why not? A soundtrack of melancholy had been playing at a low hum inside my head from the time I was 10.

但是我无法告诉你我发现我自己的失眠也许是第一个。在我失眠的斗争中,一位出色的心理药物学家告诉我,我的新病情必须是变相抑郁症。当然,我的一部分想,为什么不呢?从我10岁开始,我的脑海里一直在低矮的嗡嗡声中演奏着一群忧郁的配乐。

The thing was: I became outrageously depressed only after my insomnia began. That’s when that low hum started to blare at a higher volume. Until I stopped sleeping, I never suffered from any sadness so crippling that it prevented me from experiencing joy. It never impeded my ability to socialize or travel. It never once made me contemplate antidepressants. And it most certainly never got in the way of my sleeping. The precipitating factor in my own brutal insomnia was, and remains, an infuriating mystery.

事实是:只有在失眠开始后,我才变得沮丧。那时,那低头嗡嗡声开始以更高的量。直到我停止睡觉之前,我从未遭受过如此残酷的悲伤,以至于阻止了我感到喜悦。它从未阻碍我社交或旅行的能力。它从来没有让我考虑抗抑郁药。当然,它永远不会阻碍我睡觉。我自己残酷失眠的造成因素是并且仍然是一个令人发指的谜团。

Sleep professionals, I have learned, drink a lot of coffee. That was the first thing I noticed when I attended SLEEP 2024, the annual conference of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, in Houston: coffee, oceans of it, spilling from silver urns, especially at the industry trade show. Wandering through it was a dizzying experience, a sprawling testament to the scale and skyscraping profit margins of Big Sleep. More than 150 exhibitors showed up. Sheep swag abounded. Drug reps were everywhere, their aggression tautly disguised behind android smiles, the meds they hawked called the usual names that look like high-value Scrabble words.

睡眠专业人士,我学到了很多咖啡。那是我参加2024年睡眠时注意到的第一件事,休斯敦美国睡眠医学学院年度会议:咖啡,它的海洋,从银色的urns溢出,尤其是在行业贸易展览会上。徘徊在它的经历中令人眼花searagery乱的经历,这是对大型睡眠的规模和摩天crap脚利润的巨大证明。超过150个参展商出现了。绵羊赃物比比皆是。毒品代表无处不在,他们的侵略性在Android微笑后面扭曲,他们被鹰的药物称为通常的名字,看起来像高价值拼字游戏。

I’ve never understood this branding strategy, honestly. If you want your customers to believe they’re falling into a gentle, natural sleep, you should probably think twice before calling your drug Quviviq.

老实说,我从来没有理解这种品牌策略。如果您希望您的客户相信他们会陷入温柔,自然的睡眠中,那么您可能应该三思而后行,然后再打毒品。

I walked through the cavernous hall in a daze. It was overwhelming, really—the spidery gizmos affixed to armies of mannequins, the Times Square–style digital billboards screaming about the latest in sleep technology.

我发呆的大厅穿过海绵状大厅。确实,这是压倒性的 - 蜘蛛小孔被固定在人体模型军队中,时代广场风格的数字广告牌对最新的睡眠技术尖叫。

At some point it occurred to me that the noisy, overbusy, fluorescent quality of this product spectacular reminded me of the last place on Earth a person with a sleep disorder should be: a casino. The room was practically sunless. I saw very few clocks. After I spent an afternoon there, my circadian rhythms were shot to hell.

在某个时候,我想到,这种产品的嘈杂,过多,荧光质量使我想起了地球上最后一个患有睡眠障碍的人应该是:一个赌场。房间几乎没有阳光。我看到了很少的时钟。在我度过了一个下午之后,我的昼夜节律被枪杀了。

But the conference itself …! Extraordinary, covering miles of ground. I went to one symposium about “sleep deserts,” another about the genetics of sleep disturbance, and yet another about sleep and menopause. I walked into a colloquy about sleep and screens and had to take a seat on the floor because the room was bursting like a suitcase. Of most interest to me, though, were two panels, which I’ll shortly discuss: one about how to treat patients with anxiety from new-onset insomnia, and one on whether hypnotics are addictive.

但是会议本身……!非凡的,覆盖了数英里的地面。我去了一个关于“睡眠沙漠”的研讨会,另一个关于睡眠障碍的遗传学,而另一个关于睡眠和更年期的话题。我走进一个关于睡眠和屏幕的俗气,不得不坐在地板上,因为房间像手提箱一样爆裂。不过,我最感兴趣的是两个面板,我将很快讨论:一个关于如何治疗新的失眠症患者的患者,一个关于催眠药是否会上瘾。

My final stop at the trade fair was the alley of beauty products—relevant, I presume, because they address the aesthetic toll of sleep deprivation. Within five minutes, an energetic young salesman made a beeline for me, clearly having noticed that I was a woman of a certain age. He gushed about a $2,500 infrared laser to goose collagen production and a $199 medical-grade peptide serum that ordinarily retails for $1,100. I told him I’d try the serum. “Cheaper than Botox, and it does the same thing,” he said approvingly, applying it to the crow’s-feet around my eyes.

我在贸易展览会上的最后一站是美容产品的小巷 - 我想,因为它们解决了睡眠剥夺的美学损失。在五分钟之内,一位充满活力的年轻推销员为我做了一条直线,显然注意到我是一个年龄的女人。他涌入了大约2500美元的红外激光,用于鹅胶原蛋白生产和199美元的医用级肽血清,通常以1,100美元的价格零售。我告诉他我会尝试血清。“比肉毒杆菌毒素便宜,而且做同样的事情。”他认真地说,将其应用于我眼中的乌鸦队。

I stared in the mirror. Holy shit. The stuff was amazing.

我凝视着镜子。天哪。这些东西很棒。

“I’ll take it,” I told him.

“我会接受的,”我告诉他。

He was delighted. He handed me a box. The serum came in a gold syringe.

他很高兴。他递给我一个盒子。血清中有金注射器。

“You’re a doctor, right?”

“你是医生,对吗?”

A beat.

节拍。

“No,” I finally said. “A journalist. Can only a dermatologist—”

“不,”我终于说。“记者。只能是皮肤科医生 - ”

He told me it was fine; it’s just that doctors were his main customers. This was the sort of product women like me usually had to get from them. I walked away elated but queasy, feeling like a creep who’d evaded a background check by purchasing a Glock at a gun show.

他告诉我很好。只是医生是他的主要客户。这是像我这样的女性通常必须从她们那里得到的产品。我兴高采烈但很不安,感觉就像是一个小兵,他在枪支表演上购买了格洛克(Glock)逃避了背景调查。

The first line of treatment for chronic, intractable sleeplessness, per the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, is cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia, or CBT-I. I’ve tried it, in earnest, at two different points in my life. It generally involves six to eight sessions and includes, at minimum: identifying the patient’s sleep-wake patterns (through charts, diaries, wearables); “stimulus control” (setting consistent bedtimes and wake-up times, resisting the urge to stare at the clock, delinking the bed from anything other than sleep and sex); establishing good sleep habits (the stuff of every listicle); “sleep restriction” (compressing your sleep schedule, then slowly expanding it over time); and “cognitive restructuring,” or changing unhealthy thoughts about sleep.

根据美国睡眠医学学院的慢性,顽固性睡眠的第一道治疗是失眠的认知行为疗法或CBT-I。我认真地在生活中的两个不同点上尝试了它。它通常涉及六到八个会议,至少包括:识别患者的睡眠效果模式(通过图表,日记,可穿戴设备);“刺激控制”(设置一致的床位和唤醒时间,抵抗凝视时钟的冲动,使床与睡眠和性爱以外的任何事物脱节);建立良好的睡眠习惯(每个清单的东西);“限制睡眠”(压缩您的睡眠时间表,然后随着时间的流逝而慢慢扩展);和“认知重组”,或改变对睡眠的不健康想法。

The cognitive-restructuring component is the most psychologically paradoxical. It means taking every terrifying thing you’ve ever learned about the consequences of sleeplessness and pretending you’ve never heard them.

认知重塑成分是心理上最矛盾的。这意味着要掌握有关失眠后果的所有可怕事物,并假装自己从未听过它们。

I pointed this out to Wilfred Pigeon. “For the medically anxious, it’s tough,” he agreed. “We’re trying to tell patients two things at the same time: ‘You really need to get your sleep on track, or you will have a heart attack five years earlier than you otherwise would.’ But also: ‘Stop worrying about your sleep so much, because it’s contributing to your not being able to sleep.’ And they’re both true!”

我向威尔弗雷德鸽子指出了这一点。他同意:“对于医学上的焦虑,这很艰难。”“我们试图同时告诉患者两件事:‘您确实需要使自己的睡眠能够正常,否则您将比其他人提前五年心脏病发作。’而且:‘不要再担心自己的睡眠,因为这有助于您无法入睡。”而且他们都是真实的!”

Okay, I said. But if an insomniac crawls into your clinic after many years of not sleeping (he says people tend to wait about a decade), wouldn’t they immediately see that these two messages live in tension with each other? And dwell only on the heart attack?

好吧,我说。但是,如果失眠后多年没有睡觉后进入您的诊所(他说人们倾向于等待大约十年),他们会不会立即看到这两条消息彼此之间存在紧张感吗?只居住在心脏病上?

“I tell the patient their past insomnia is water under the bridge,” Pigeon said. “We’re trying to erase the added risks that ongoing chronic insomnia will have. Just because a person has smoked for 20 years doesn’t mean they should keep smoking.”

鸽子说:“我告诉病人他们过去的失眠是桥下的水。”“我们正在努力消除持续的慢性失眠的额外风险。仅仅因为一个人吸烟了20年,并不意味着他们应该继续吸烟。”

He’s absolutely right. But I’m not entirely convinced that these incentives make the cognitive dissonance of CBT-I go away. When Sara Nowakowski, a CBT-I specialist at Baylor College of Medicine, gave her presentation at SLEEP 2024’s panel on anxiety and new-onset insomnia, she said that many of her patients start reciting the grim data from their Fitbits and talking about dementia.

他是绝对正确的。但是,我并不完全相信这些激励措施使我消失了CBT-I的认知失调。当Baylor医学院的CBT-I专家Sara Nowakowski在2024年Sleep 2024的《焦虑和新发作失眠》小组上发表了她的演讲时,她说,她的许多患者开始朗诵他们的Fitbits的严峻数据并谈论痴呆症。

That’s likely because they’ve read the studies. Rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep, that vivid-dream stage when our eyes race beneath our eyelids like mice under a blanket, is essential to emotional regulation and problem-solving. Slow-wave sleep, our deepest sleep, is essential for repairing our cells, shoring up our immune systems, and rinsing toxins from our brains, thanks to a watery complex of micro-canals called the glymphatic system. We repair our muscles when we sleep. We restore our hearts. We consolidate memories and process knowledge, embedding important facts and disposing of trivial ones. We actually learn when we’re asleep.

这可能是因为他们已经阅读了研究。快速眼动(REM)睡眠,当我们的眼睛像毯子下的小鼠一样在眼皮下面时,这对于情绪调节和解决问题至关重要。慢波睡眠是我们最深的睡眠,对于修复细胞,支撑我们的免疫系统并从大脑中冲洗毒素至关重要,这要归功于称为淋巴系统的微型植物配合物。睡觉时我们修复肌肉。我们恢复我们的心。我们巩固了记忆和过程知识,嵌入重要事实并处理琐碎的事实。我们实际上在睡觉时学习。

Many insomniacs know all too well how nonnegotiably vital sleep is, and what the disastrous consequences are if you don’t get it. I think of the daredevil experiment that Nathaniel Kleitman, the father of sleep research, informally conducted as a graduate student in 1922, enlisting five classmates to join him in seeing how long they could stay awake. He lasted the longest—a staggering 115 hours—but at a terrible price, temporarily going mad with exhaustion, arguing on the fifth day with an imaginary foe about the need for organized labor. And I think of Allan Rechtschaffen, another pioneer in the field, who in 1989 had the fiendish idea to place rats on a spinning mechanism that forced them to stay awake if they didn’t want to drown. They eventually dropped dead.

许多失眠症都非常了解无效的睡眠是多么重要,如果您不明白,灾难性的后果是什么。我想到了夜魔侠实验,睡眠研究的父亲纳撒尼尔·克莱特曼(Nathaniel Kleitman)于1922年非正式地担任研究生,并邀请五名同学与他一起,看到他们可以保持清醒多长时间。他持续了最长的115个小时,但价格可怕,暂时使疲惫生气,在第五天与想象中的敌人争论有组织的劳动。我想到了该领域的另一位先驱艾伦·雷赫(Allan Rechtschaffen),他在1989年有一个邪恶的想法将老鼠放在旋转机制上,如果他们不想淹死,迫使他们保持清醒状态。他们最终死了。

So these are the kinds of facts a person doing CBT-I has to ignore.

因此,这些是一个人必须忽略的事实。

Still. Whether a patient’s terrors concern the present or the future, it is the job of any good CBT-I practitioner to help fact-check or right-size them through Socratic questioning. During her panel at SLEEP 2024, Nowakowski gave very relatable examples:

仍然。无论患者的恐怖涉及现在还是未来,无论CBT-I从业人员的工作都是通过苏格拉底询问来帮助事实检查或右派大小的工作。在2024年睡觉的小组讨论期间,Nowakowski举了非常相关的例子:

When you’re struggling to fall asleep, what are you most worried will happen?

当您努力入睡时,您最担心的会发生什么?

I’ll lose my job/scream at my kids/detonate my relationship/never be able to sleep again.

我会失去工作/尖叫的孩子/引爆我的恋爱关系/再也无法入睡。

And what’s the probability of your not falling asleep?

您没有入睡的可能性是什么?

I don’t sleep most nights.

我大多数晚上都不睡觉。

And the probability of not functioning at work or yelling at the kids if you don’t?

以及如果不工作或对孩子大喊大叫的可能性?

Ninety percent.

百分之九十。

She then tells her patients to go read their own sleep diary, which she’s instructed them to keep from the start. The numbers seldom confirm they’re right, because humans are monsters of misprediction. Her job is to get her patients to start decatastrophizing, which includes what she calls the “So what?” method: So what if you have a bad day at work or at home? You’ve had others. Will it be the end of the world? (When my second CBT-I therapist asked me this, I silently thought, Yes, because when I’m dangling at the end of my rope, I just spin more.) CBT-I addresses anxiety about not sleeping, which tends to be the real force that keeps insomnia airborne, regardless of what lofted it. The pre-sleep freaking out, the compulsive clock-watching, the bargaining, the middle-of-the-night doom-prophesizing, the despairing—CBT-I attempts to snip that loop. The patient actively learns new behaviors and attitudes to put an end to their misery.

然后,她告诉患者去阅读自己的睡眠日记,她指示他们从一开始就保持。数字很少证实它们是对的,因为人类是错误预测的怪物。她的工作是让她的患者开始脱发,其中包括她所说的“那呢?”方法:如果您在工作或在家中度过糟糕的一天,该怎么办?你有别人。它将是世界的尽头吗?(当我的第二个CBT-I治疗师问我这个问题时,我默默地想,是的,因为当我在绳索末端悬挂时,我只是旋转更多。)CBT-I解决了对不睡觉的焦虑,这往往是保持失眠的空气生气的真实力量,无论它不管是什么。前袖口吓坏了,强迫性时钟,议价,中间的末日末日求职,绝望的 - cbt-i试图削减该循环。患者积极学习新的行为和态度,以结束痛苦。

But the main anchor of CBT-I is sleep-restriction therapy. I tried it back when I was 29, when I dragged my wasted self into a sleep clinic in New York; I’ve tried it once since. I couldn’t stick with it either time.

但是CBT-I的主要锚是睡眠限制疗法。29岁时,当我将浪费的自我拖入纽约的睡眠诊所时,我尝试了一下。从那以后我尝试过一次。我都不能坚持这一点。

The concept is simple: You severely limit your time in bed, paring away every fretful, superfluous minute you’d otherwise be awake. If you discover from a week’s worth of sleep-diary entries (or your wearable) that you spend eight hours buried in your duvet but sleep for only five of them, you consolidate those splintered hours into one bloc of five, setting the same wake-up time every day and going to bed a mere five hours before. Once you’ve averaged sleeping those five hours for a few days straight, you reward your body by going to bed 15 minutes earlier. If you achieve success for a few days more, you add another 15 minutes. And then another … until you’re up to whatever the magic number is for you.

这个概念很简单:您严重限制了床上的时间,削减了每一个烦躁,多余的分钟,否则您会醒着。如果您从一周的睡眠界条目(或您的可穿戴设备)中发现,您花了八个小时埋葬在羽绒被,但只能睡五个小时,您可以将这些小时的小时整合到一个五个小时的五个小时中,每天将相同的唤醒时间设置在五个小时前的睡觉。一旦您平均这五个小时连续几天睡觉,您就可以在15分钟前上床睡觉来奖励身体。如果您获得了几天的成功,则又增加了15分钟。然后是另一个……直到您掌握任何魔术数字为您服务。

No napping. The idea is to build up enough “sleep pressure” to force your body to collapse in surrender.

没有小睡。这个想法是建立足够的“睡眠压力”,以迫使您的身体在投降中崩溃。

Sleep restriction can be a wonderful method. But if you have severe insomnia, the idea of reducing your sleep time is petrifying. Technically, I suppose, you’re not really reducing your sleep time; you’re just consolidating it. But practically speaking, you are reducing your sleep, at least in the beginning, because dysregulated sleep isn’t an accordion, obligingly contracting itself into a case. Contracting it takes time, or at least it did for me. The process was murder.

睡眠限制可能是一种绝妙的方法。但是,如果您患有严重的失眠,减少睡眠时间的想法就是质量。从技术上讲,我想,您并没有真正减少睡眠时间;您只是在整合它。但是实际上,至少在一开始,您正在减少睡眠,因为睡眠不足不是手风琴,而是将自己纳入案例。收缩需要时间,或者至少对我有所帮助。这个过程是谋杀。

“If you get people to really work their way through it—and sometimes that takes holding people’s hands—it ends up being more effective than a pill,” Ronald Kessler, a renowned psychiatric epidemiologist at Harvard, told me when I asked him about CBT-I. The problem is the formidable size of that if. “CBT-I takes a lot more work than taking a pill. So a lot of people drop out.”

“如果您让人们真正通过它来努力 - 有时握住人们的手 - 最终比药丸更有效,”哈佛大学著名的精神病学家罗纳德·凯斯勒(Ronald Kessler)告诉我,当我问他有关CBT-I的问题时。问题是如果它的大小。“ CBT-I比服用药丸要做的工作要多得多。因此,很多人辍学了。”

They do. One study I perused had an attrition rate of 40 percent.

他们这样做。我仔细研究的一项研究的损耗率为40%。

Twenty-six years ago, I, too, joined the legions of the quitters. In hindsight, my error was my insistence on trying this grueling regimen without a benzodiazepine (Valium, Ativan, Xanax), though my doctor had recommended that I start one. But I was still afraid of drugs in those days, and I was still in denial that I’d become hostage to my own brain’s terrorism. I was sure that I still had the power to negotiate. Competence had until that moment defined my whole life. I persuaded the doctor to let me try without drugs.

二十六年前,我也加入了戒烟者的军团。事后看来,我的错误是我坚持尝试这种艰苦的方案,而没有苯二氮卓(Valium,ativan,xanax),尽管我的医生建议我开始一个。但是那时我仍然害怕毒品,而且我仍然否认自己会成为自己的大脑恐怖主义的人质。我确定我仍然有权谈判。直到那一刻,能力才定义了我的一生。我说服了医生让我尝试不吸毒。

As she’d predicted, I failed. The graphs in my sleep diary looked like volatile weeks on the stock exchange.

正如她预测的那样,我失败了。我的睡眠日记中的图形看起来像是在证券交易所上的挥发性周。

For the first time ever, I did need an antidepressant. The doctor wrote me a prescription for Paxil and a bottle of Xanax to use until I got up to cruising altitude—all SSRIs take a while to kick in.

有史以来我第一次需要抗抑郁药。医生给我写了一份为Paxil和一瓶Xanax的处方,直到我提高巡航高度为止 - 所有SSRI都需要一段时间才能开始。

I didn’t try sleep restriction again until many years later. Paxil sufficed during that time; it made me almost stupid with drowsiness. I was sleepy at night and vague during the day. I needed Xanax for only a couple of weeks, which was just as well, because I didn’t much care for it. The doctor had prescribed too powerful a dose, though it was the smallest one. I was such a rookie with drugs in those days that it never occurred to me I could just snap the pill in half.

直到很多年后,我才尝试再次尝试睡眠限制。Paxil在那段时间就足够了;这使我昏昏欲睡几乎愚蠢。我晚上很困,白天含糊不清。我只需要几周的Xanax,这也一样,因为我不太在乎它。医生开了强大的剂量,尽管它是最小的剂量。在那些日子里,我真是个新秀,毒品,以至于我从来没有想过,我只能将药丸一半。

Have I oversimplified the story of my insomnia? Probably. At the top of the SLEEP 2024 panel about anxiety and new-onset insomnia, Leisha Cuddihy, a director at large for the Society of Behavioral Sleep Medicine, said something that made me wince—namely, that her patients “have a very vivid perception of pre-insomnia sleep being literally perfect: ‘I’ve never had a bad night of sleep before now.’ ”

我是否过于简化失眠的故事?大概。在2024年睡眠的顶部关于焦虑和新发作失眠的面板上,行为睡眠医学协会的主任莱莎·库迪迪(Leisha Cuddihy)说,让我感到畏缩的某些事情,即她的患者“从未有过非常完美的睡眠,我的病人很完美:我从来没有过一个糟糕的睡眠:我在现在睡过了不好的睡眠。”

Okay, guilty as charged. While it’s true that I’d slept brilliantly (and I stand by this, brilliantly) in the 16 years before I first sought help, I was the last kid to fall asleep at slumber parties when I was little. Cuddihy also said that many of her patients declare they’re certain, implacably certain, that they are unfixable. “They feel like something broke,” she said.

好吧,有罪。虽然我第一次寻求帮助的16年来,我很出色地睡过(我坚定地站在这个方面),但我是一个小时候在沉睡的聚会上入睡的孩子。Cuddihy还说,她的许多患者宣称他们可以肯定,可以肯定的是,他们是无法使用的。她说:“他们觉得有些事情破裂了。”

Which is what I wrote just a few pages back. Poisoned, broke, same thing.

这就是我写的几页。中毒,破裂,同样的事情。

By the time Cuddihy finished speaking, I had to face an uncomfortable truth: I was a standard-issue sleep-clinic zombie.

到Cuddihy说话结束时,我不得不面对一个不舒服的事实:我是标准发行的睡眠式僵尸。

But when patients say they feel like something broke inside their head, they aren’t necessarily wrong. An insomniac’s brain does change in neurobiological ways.

但是,当病人说他们觉得自己的脑海中破裂时,他们不一定是错误的。失眠的大脑确实会以神经生物学方式改变。

“There is something in the neurons that’s changing during sleep in patients with significant sleep disruptions,” said Eric Nofzinger, who, while at the University of Pittsburgh, had one of the world’s largest databases of brain-imaging studies of sleeping human beings. “If you’re laying down a memory, then that circuitry is hardwired for that memory. So one can imagine that if your brain is doing this night after night …”

埃里克·诺夫辛格(Eric Nofzinger)在匹兹堡大学(University of Pittsburgh University of Pittsburgh)中说:“神经元中的神经元中有些在睡眠中发生变化。”“如果您要放下记忆,那么该电路是为了记忆而刻连接的。因此,人们可以想象,如果您的大脑在黑夜又一个夜晚在做……”

We know that the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, our body’s first responder to stress, is overactivated in the chronically underslept. If the insomniac suffers from depression, their REM phase tends to be longer and more “dense,” with the limbic system (the amygdala, the hippocampus—where our primal drives are housed) going wild, roaring its terrible roars and gnashing its terrible teeth. (You can imagine how this would also make depressives subconsciously less motivated to sleep—who wants to face their Gorgon dreams?) Insomniacs suffering from anxiety experience this problem too, though to a lesser degree; it’s their deep sleep that’s mainly affected, slimming down and shallowing out.

我们知道,在慢性底层下,下丘脑 - 垂体 - 肾上腺轴是压力的第一响应者。如果失眠症患有抑郁症,它们的REM期往往会更长,更“密集”,边缘系统(杏仁核,海马,海马,我们的原始驱动器被安置在那里),咆哮着咆哮,咆哮着,牙齿可怕。(您可以想象这也会使抑郁症在潜意识中减少入睡的动力 - 谁想要面对他们的戈贡梦?)失眠症患有焦虑症也经历了这个问题,尽管程度较小。他们的深度睡眠主要受到影响,苗条并降低。

And in all insomniacs, throughout the night, the arousal centers of the brain keep clattering away, as does the prefrontal cortex (in charge of planning, decision making), whereas in regular sleepers, these buzzing regions go offline. “So when someone with insomnia wakes up the next morning and says, ‘I don’t think I slept at all last night,’ in some respects, that’s true,” Nofzinger told me. “Because the parts of the brain that should have been resting did not.”

在所有失眠症中,整个晚上,大脑的唤醒中心不断散步,前额叶皮层(负责计划,决策)也是如此,而在常规的卧铺中,这些嗡嗡声偏离线。“因此,当第二天早上失眠的人醒来时说,‘我认为昨晚我根本不睡觉,’在某些方面,这是真的,” Nofzinger告诉我。“因为应该休息的大脑部分没有。”

And why didn’t they rest? The insomniac can’t say. The insomniac feels at once responsible and helpless when it comes to their misery: I must be to blame. But I can’t be to blame. The feeling that sleeplessness is happening to you, not something you’re doing to yourself, sends you on a quest for nonpsychological explanations: Lots of physiological conditions can cause sleep disturbances, can’t they? Obstructive sleep apnea, for instance, which afflicts nearly 30 million Americans. Many autoimmune diseases, too. At one point, I’ll confess that I started asking the researchers I spoke with whether insomnia itself could be an autoimmune disorder, because that’s what it feels like to me—as if my brain is going after itself with brickbats.

他们为什么不休息?失眠不能说。当涉及到他们的痛苦时,失眠症立即感到责任和无助:我必须责备。但是我不能怪。失眠正在发生的感觉,而不是您对自己所做的事情,这会让您寻求非心理学解释:很多生理状况会导致睡眠障碍,不是吗?例如,阻塞性睡眠呼吸暂停会遭受近3000万美国人的困扰。许多自身免疫性疾病也是如此。有一次,我承认我开始问我谈论的研究人员与失眠本身是否可能是一种自身免疫性疾病,因为这对我来说就是感觉 - 就像我的大脑在Brickbats上自然而然。

“Narcolepsy appears to be an example of a sleep disorder involving the immune system,” Andrew Krystal, a psychiatrist specializing in sleep disorders at UCSF, told me.

“睡病似乎是涉及免疫系统的睡眠障碍的一个例子,”专门从事UCSF睡眠障碍的精神科医生安德鲁·克里斯塔尔(Andrew Krystal)告诉我。

What? I said. Really?

什么?我说。真的吗?

Really, he replied. “There are few things I know of,” he said, “that are as complicated as the mammalian immune system.”

真的,他回答。他说:“我知道的事情很少,就像哺乳动物免疫系统一样复杂。”

But insomnia-as-autoimmune-disorder is only a wisp of a theory, a wish of a theory, nothing more. In her memoir, The Shapeless Unease: A Year of Not Sleeping, the novelist Samantha Harvey casts around for a physiological explanation, too. But after she completes a battery of tests, the results come back normal, pointing to “what I already know,” she writes, “which is that my sleeplessness is psychological. I must carry on being the archaeologist of myself, digging around, seeing if I can excavate the problem and with it the solution—when in truth I am afraid of myself, not of what I might uncover, but of managing to uncover nothing.”

但是,失眠 - 自动免疫性疾病只是一种理论的意识,仅是理论的愿望,仅此而已。在她的回忆录中,无形的不安:一年不睡觉的一年,小说家萨曼莎·哈维(Samantha Harvey)也四处张望生理解释。但是,在她完成了一系列测试后,结果恢复正常,指出“我已经知道的东西”,她写道:“那是我的失眠是心理的。我必须继续成为自己的考古学家,四处逛逛,挖掘出来,看看我能挖掘出这个问题,而解决方案是否可以解决问题 - 实际上,我害怕自己,而不是我可以洞察到任何东西,但我会遇到任何东西,但要忽略任何事情。

Armando Veve

Armando Veve

I didn’t tolerate my Paxil brain for long. I weaned myself off, returned to normal for a few months, and assumed that my sleeplessness had been a freak event, like one of those earthquakes in a city that never has them. But then my sleep started to slip away again, and by age 31, I couldn’t recapture it without chemical assistance. Prozac worked for years on its own, but it blew out whatever circuit in my brain generates metaphors. When I turned to the antidepressants that kept the electricity flowing, I needed sleep medication too—proving, to my mind, that melancholy couldn’t have been the mother of my sleep troubles, but the lasting result of them. I’ve used the lowest dose of Klonopin to complement my SSRIs for years. In times of acute stress, I need a gabapentin or a Unisom too.

我没有忍受长时间的帕西尔大脑。我断奶了,恢复了几个月,并认为我的失眠是一个怪异事件,就像一个从未有过的城市中的地震之一一样。但是随后我的睡眠再次开始溜走,到31岁时,我无法在没有化学援助的情况下恢复它。Prozac独自工作了多年,但它炸毁了我大脑中的任何电路都会产生隐喻。当我转向保持电力流动的抗抑郁药时,我也需要睡眠药物 - 在我看来,忧郁的母亲不可能是我睡眠麻烦的母亲,而是它们的持久结果。多年来,我使用了最低剂量的克洛诺平剂量来补充我的SSRI。在急性压力的时候,我也需要加巴喷丁或单身。

Unisom is fine. Gabapentin also turns my mind into an empty prairie.

Unisom很好。加巴喷丁也将我的思想变成了一个空的草原。

Edibles, which I’ve also tried, turn my brain to porridge the next day. Some evidence suggests that cannabis works as a sleep aid, but more research, evidently, is required. (Sorry.)

我也尝试过的食物,第二天将我的大脑变成粥。一些证据表明,大麻是一种睡眠援助,但显然需要更多的研究。(对不起。)

Which brings me to the subject of drugs. I come neither to praise nor to bury them. But I do come to reframe the discussion around them, inspired by what a number of researcher-clinicians said about hypnotics and addiction during the SLEEP 2024 panel on the subject. They started with a simple question: How do you define addiction?

这使我成为毒品的主题。我既不来赞美也不埋葬他们。但是,我确实是为了重新构架周围的讨论,这是受到许多研究人员访问者对2024年睡眠小组讨论的催眠和成瘾的启发的启发。他们从一个简单的问题开始:您如何定义成瘾?

It’s true that many of the people who have taken sleep medications for months or years rely on them. Without them, the majority wouldn’t sleep, at least in the beginning, and a good many would experience rebound insomnia if they didn’t wean properly, which can be even worse. One could argue that this dependence is tantamount to addiction.

的确,服用了几个月或数年的睡眠药物的许多人都依靠它们。没有他们,至少在一开始,大多数人就不会入睡,如果他们不正确地断裂,很多人会遇到反弹的失眠症,这可能会更糟。有人可能会争辩说,这种依赖性与成瘾有关。

But: We don’t say people are addicted to their hypertension medication or statins, though we know that in certain instances lifestyle changes could obviate the need for either one. We don’t say people are addicted to their miracle GLP-1 agonists just because they could theoretically diet and exercise to lose weight. We agree that they need them. They’re on Lasix. On Lipitor. On Ozempic. Not addicted to.

但是:我们并不是说人们沉迷于他们的高血压药物或他汀类药物,尽管我们知道在某些情况下,生活方式的改变可能会消除任何一种需求。我们并不是说人们沉迷于奇迹GLP-1激动剂,只是因为他们可以从理论上节食和运动来减肥。我们同意他们需要它们。他们在lasix上。在Lipitor上。在Ozempic上。不上瘾。

Yet we still think of sleep medications as “drugs,” a word that in this case carries a whiff of stigma—partly because mental illness still carries a stigma, but also because sleep medications legitimately do have the potential for recreational use and abuse.

然而,我们仍然将睡眠药物视为“药物”,在这种情况下,这个词会带来污名化 - 部分是因为精神疾病仍然带有污名,但这也是因为合法的睡眠药物确实具有娱乐使用和虐待的可能性。

But is that what most people who suffer from sleep troubles are doing? Using their Sonata or Ativan for fun?

但是,大多数患有睡眠困扰的人都在做什么?使用他们的奏鸣曲或ativan玩得开心?

“If you see a patient who’s been taking medication for a long time,” Tom Roth, the founder of the Sleep Disorders and Research Center at Henry Ford Hospital, said during the panel, “you have to think, ‘Are they drug-seeking or therapy-seeking ?’ ” The overwhelming majority, he and other panelists noted, are taking their prescription drugs for relief, not kicks. They may depend on them, but they’re not abusing them—by taking them during the day, say, or for purposes other than sleep.

亨利·福特医院(Henry Ford Hospital)的睡眠障碍和研究中心的创始人汤姆·罗斯(Tom Roth)在小组中说:“如果您看到一位服用了很长时间的病人,”他和其他小组成员们在接受处方药,而不是踢出处方药。它们可能依靠它们,但没有滥用它们 - 通过白天或出于睡眠以外的其他目的,他们会滥用它们。

Still, let’s posit that many long-term users of sleep medication do become dependent. Now let’s consider another phenomenon commonly associated with reliance on sleep meds: You enter Garland and Hendrix territory in a hurry. First you need one pill, then you need two; eventually you need a fistful with a fifth of gin.

不过,让我们认为,许多长期睡眠药物的长期用户确实会依赖。现在,让我们考虑另一个与依赖睡眠药物有关的现象:您急忙进入Garland和Hendrix领土。首先,您需要一种药丸,然后您需要两颗;最终,您需要用五分之一的杜松子酒拳头。

Yet a 2024 cohort study, which involved nearly 1 million Danes who used benzodiazepines long-term, found that of those who used them for three years or more—67,398 people, to be exact—only 7 percent exceeded their recommended dose.

然而,一项2024年的队列研究涉及近100万丹麦人长期使用苯二氮卓类药物的丹麦人,发现那些使用它们三年或更长时间的人(准确地说是67,398人)超过了他们推荐的剂量。

Not a trivial number, certainly, if you’re staring across an entire population. But if you’re evaluating the risk of taking a hypnotic as an individual, you’d be correct to assume that your odds of dose escalation are pretty low.

当然,如果您盯着整个人口,这并不是一个琐碎的数字。但是,如果您要评估将催眠的风险作为一个人,那么您可以正确地假设剂量升级的几率相当低。

That there’s a difference between abuse and dependence, that dependence doesn’t mean a mad chase for more milligrams, that people depend on drugs for a variety of other naturally reversible conditions and don’t suffer any stigma—these nuances matter.

滥用和依赖之间存在差异,依赖性并不意味着要对更多毫克的疯狂追逐,人们依靠药物来依靠其他自然可逆的疾病,并且不会遭受任何污名 - 这些细微差别很重要。

“Using something where the benefits outweigh the side effects certainly is not addiction,” Winkelman, the Harvard psychiatrist and chair of the panel, told me when we spoke a few months later. “I call that treatment.”

哈佛大学的精神科医生兼小组主席温克尔曼(Winkelman)在几个月后讲话时告诉我:“使用副作用肯定超过副作用的东西肯定不是上瘾。”“我称这种治疗。”

The problem, he told me, is when the benefits stop outweighing the downsides. “Let’s say the medication loses efficacy over time.” Right. That 7 percent. And over-the-counter sleep meds, whose active component is usually diphenhydramine (more commonly known as Benadryl), are potentially even more likely to lose their efficacy—the American Academy of Sleep Medicine advises against them. “And let’s say you did stop your medication,” Winkelman continued. “Your sleep could be worse than it was before you started it,” at least for a while. “People should know about that risk.”

他告诉我,问题是当福利停止胜过弊端时。“假设药物随着时间的流逝而失去疗效。”正确的。那7%。非处方的睡眠药物的活性成分通常是二苯胺(通常称为贝纳德利尔),甚至可能更有可能失去疗效 - 美国睡眠医学学会建议对他们提出。“假设您确实停止了药物,” Winkelman继续说道。“您的睡眠可能比开始之前的睡眠更糟,”至少有一段时间。“人们应该知道这种风险。”

A small but even more hazardous risk: a seizure, for those who abruptly stop taking high doses of benzodiazepines after they’ve been on them for a long period of time. The likelihood is low—the exact percentage is almost impossible to ascertain—but any risk of a seizure is worth knowing about. “And are you comfortable with the idea that the drug could irrevocably be changing your brain?” Winkelman asked. “The brain is a machine, and you’re exposing it to the repetitive stimulus of the drug.” Then again, he pointed out, you know what else is a repetitive stimulus? Insomnia.

一个很小但更危险的风险:癫痫发作,对于那些在长时间出现的人之后突然停止服用高剂量的苯二氮卓类药物的人。可能性很低(几乎无法确定的确切百分比),但是任何癫痫发作的风险都值得知道。“您是否对这种药物可以不可撤销地改变您的大脑的想法感到满意?”温克尔曼问。“大脑是一台机器,您将其暴露于药物的重复刺激中。”然后,他再次指出,您知道还有什么是重复的刺激?失眠。

“So should these things even be considered a part of an addiction?” he asked. “At what point does a treatment become an addiction? I don’t know.”

“那么这些事情甚至应该被视为成瘾的一部分吗?”他问。“在什么时候治疗成为成瘾?我不知道。”

Calvinist about sleep meds, blasé about sleep meds—whatever you are, the fact remains: We’re a nation that likes them. According to a 2020 report from the National Center for Health Statistics, 8.4 percent of Americans take sleep medications most nights or every night, and an additional 10 percent take them on some. Part of the reason medication remains so popular is that it’s easy for doctors to prescribe a pill and give a patient immediate relief, which is often what patients are looking for, especially if they’re in extremis or need some assistance through a rough stretch. CBT‑I, as Ronald Kessler noted, takes time to work. Pills don’t.

关于睡眠药物的加尔文主义者,关于睡眠药物的蓝色,无论您是什么,事实仍然是:我们是一个喜欢他们的国家。根据国家卫生统计中心2020年的一份报告,有8.4%的美国人大部分晚上或每天晚上都服用睡眠药物,而另外10%的美国人则将它们带到一些。药物如此受欢迎的部分原因是,医生很容易开药并立即给患者提供救济,这通常是患者正在寻找的东西,尤其是当他们处于极端状态或在艰难的情况下需要一些帮助。正如罗纳德·凯斯勒(Ronald Kessler)指出的那样,CBT ‑ I需要时间上班。药丸没有。

But another reason, as Suzanne Bertisch pointed out during the addiction-and-insomnia-meds panel, is that “primary-care physicians don’t even know what CBT-I is. This is a failure of our field.”

但是,正如苏珊娜·贝蒂奇(Suzanne Bertisch)在成瘾和insomnia-meds小组中指出的那样,另一个原因是“初级保健医生甚至都不知道CBT-I是什么。这是我们领域的失败。”

Even if general practitioners did know about CBT-I, too few therapists are trained in it, and those who are tend to have fully saturated schedules. The military, unsurprisingly, has tried to work around this problem (sleep being crucial to soldiers, sedatives being contraindicated in warfare) with CBT-I via video as well as an online program, both shown to be efficacious. But most of us are not in the Army. And while some hospitals, private companies, and the military have developed apps for CBT-I too, most people don’t know about them.

即使全科医生确实知道CBT-I,也很少接受治疗师的培训,而那些往往有完全饱和的时间表的治疗师。毫不奇怪,军方试图通过CBT-I通过视频以及在线计划来解决这个问题(睡眠对士兵至关重要,在战争中禁忌镇静剂,在战争中被禁用),这两者都证明是有效的。但是我们大多数人都不在军队中。尽管一些医院,私人公司和军方也为CBT-I开发了应用程序,但大多数人对此不了解。

For years, medication has worked for me. I’ve stopped beating myself up about it. If the only side effect I’m experiencing from taking 0.5 milligrams of Klonopin is being dependent on 0.5 milligrams of Klonopin, is that really such a problem?

多年来,药物一直对我有用。我已经不再殴打自己了。如果我从0.5毫克klonopin中遇到的唯一副作用依赖于0.5毫克klonopin,那真的是一个问题吗?

There’s been a lot of confusing noise about sleep medication over the years. “Weak science, alarming FDA black-box warnings, and media reporting have fueled an anti-benzodiazepine movement,” says an editorial in the March 2024 issue of The American Journal of Psychiatry. “This has created an atmosphere of fear and stigma among patients, many of whom can benefit from such medications.”

多年来,睡眠药物有很多令人困惑的噪音。“弱科学,令人震惊的FDA Black-Box警告和媒体报道助长了反杂化的运动,” 2024年3月的《美国精神病学杂志》上的社论说。“这给患者带来了恐惧和污名的氛围,其中许多可以从这种药物中受益。”

A case in point: For a long time, the public believed that benzodiazepines dramatically increased the risk of Alzheimer’s disease, thanks to a 2014 study in the British Medical Journal that got the usual five-alarm-fire treatment by the media. Then, two years later, another study came along, also in the British Medical Journal, saying, Never mind, nothing to see here, folks; there appears to be no causal relationship we can discern.

一个很好的例子:很长一段时间以来,公众认为苯二氮卓类药物急剧增加了阿尔茨海默氏病的风险,这要归功于2014年在《英国医学杂志》上进行的一项研究,该研究得到了媒体的常见五种警报治疗。然后,两年后,另一项研究也在《英国医学杂志》中进行,说,没关系,在这里什么都看不见,伙计们。我们似乎没有因果关系。

That study may one day prove problematic, too. But the point is: More work needs to be done.

这项研究也可能有问题。但关键是:需要做更多的工作。

A different paper, however—again by Daniel Kripke, the fellow who argued that seven hours of sleep a night predicted the best health outcomes—may provide more reason for concern. In a study published in 2012, he looked at more than 10,000 people on a variety of sleep medications and found that they were several times more likely to die within 2.5 years than a matched cohort, even when controlling for a range of culprits: age, sex, alcohol use, smoking status, body-mass index, prior cancer. Those who took as few as 18 pills a year had a 3.6-fold increase. (Those who took more than 132 had a 5.3-fold one.)

然而,与丹尼尔·克里普克(Daniel Kripke)同时,一份不同的论文,他认为七个小时的睡眠预测了最好的健康状况 - 也可能会引起更多关注的理由。在2012年发表的一项研究中,他研究了10,000多人正在接受各种睡眠药物,发现它们在2.5岁之内死亡的可能性要比匹配的队列高出几倍,即使在控制一系列罪魁祸首时,他们也要死亡:年龄,性别,性饮酒,吸烟状况,身体量,身体量指数,先前的癌症。那些每年只服用18颗丸的人增加了3.6倍。(那些服用超过132人的人有5.3倍。)

John Winkelman doesn’t buy it. “Really,” he told me, “what makes a lot more sense is to ask, ‘Why did people take these medications in the first place?’ ” And for what it’s worth, a 2023 study funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse and published in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that people on stable, long-term doses of a benzodiazepine who go off their medication have worse mortality rates in the following 12 months than those who stay on it. So maybe you’re damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

约翰·温克尔曼(John Winkelman)不买。他告诉我:“真的,更有意义的是问,‘为什么人们首先服用这些药物?’”,其价值是什么,这是一项由美国国家药物滥用研究所资助的2023年研究,并在《美国医学协会杂志》上发表在《美国医学协会杂志》上,人们发现,稳定的,长期剂量的苯并二氮杂的人都在甲唑迪亚兹ep以下的人差不多。因此,如果您这样做的话,也许您该死的,如果不这样做。

Still, I take Kripke’s study seriously. Because … well, Christ, I don’t know. Emotional reasons? Because other esteemed thinkers still think there’s something to it?

尽管如此,我还是认真对待Kripke的研究。因为……好吧,基督,我不知道。情感原因?因为其他受人尊敬的思想家仍然认为有什么?

In my own case, the most compelling reasons to get off medication are the more mundane ones: the scratchy little cognitive impairments it can cause during the day, the risk of falls as you get older. (I should correct myself here: Falling when you’re older has the potential to be not mundane, but very bad.) Medications can also cause problems with memory as one ages, even if they don’t cause Alzheimer’s, and the garden-variety brain termites of middle and old age are bummer enough.

就我本身而言,放弃药物的最引人注目的理由是更平凡的人:白天可能造成的小小的认知障碍,随着年龄的增长,跌倒的风险。(我应该在这里纠正自己:年纪大的时候跌倒有可能不是平凡的,但非常糟糕。)药物也可能导致一个年龄的记忆问题,即使它们不会引起阿尔茨海默氏症,而花园中期和老年的花园危险脑白蚁也足够令人垂涎。

And maybe most generally: Why have a drug in your system if you can learn to live without it?

也许最普遍的是:如果您可以学会没有它的生活,为什么要在系统中使用药物?

My suspicion is that most people who rely on sleep drugs would prefer natural sleep.

我的怀疑是,大多数依靠睡眠药物的人都喜欢自然的睡眠。

So yes: I’d love to one day make a third run at CBT-I, with the hope of weaning off my medication, even if it means going through a hell spell of double exhaustion. CBT-I is a skill, something I could hopefully deploy for the rest of my life. Something I can’t accidentally leave on my bedside table.

所以是的:我很想有一天在CBT-I进行第三次跑步,希望断奶我的药物,即使这意味着要经历双重疲惫的地狱。CBT-I是一项技能,我希望在余生中都可以部署。我不能不小心留在床头柜上。

Some part of me, the one that’s made of pessimism, is convinced that it won’t work no matter how long I stick with it. But Michael Irwin, at UCLA, told me something reassuring: His research suggests that if you have trouble with insomnia or difficulty maintaining your sleep, mindfulness meditation while lying in bed can be just as effective as climbing out of bed, sitting in a chair, and waiting until you’re tired enough to crawl back in—a pillar of CBT‑I, and one that I absolutely despise. I do it sometimes, because I know I should, but it’s lonely and freezing, a form of banishment.

我的某些部分是悲观的,它坚信,无论我坚持多长时间,它都不会起作用。但是在加州大学洛杉矶分校(UCLA)的迈克尔·欧文(Michael Irwin)告诉我一些令人放心的事情:他的研究表明,如果您在失眠或难以维持睡眠方面遇到麻烦,躺在床上时的正念冥想与从床上爬上床,坐在椅子上,等待到足以让您疲倦地回来时,我绝对是cbt -i的crail,我绝对是我的cbt − bill of cbt -i,我都会感到沮丧。有时我会这样做,因为我知道我应该这样做,但是这是一种寂寞而冻结的,一种放逐的形式。

And if CBT-I doesn’t work, Michael Grandner, the director of the sleep-and-health-research program at the University of Arizona, laid out an alternative at SLEEP 2024: acceptance and commitment therapy, or ACT. The basic idea is exactly what the name suggests. You accept your lot. You change exactly nothing. If you can’t sleep, or you can’t sleep enough, or you can sleep only in a broken line, you say, This is one of those things I can’t control. (One could see how such a mantra might help a person sleep, paradoxically.) You then isolate what matters to you. Being functional the next day? Being a good parent? A good friend? If sleep is the metaphorical wall you keep ramming your head against, “is your problem the wall?” Grandner asked. “Or is your problem that you can’t get beyond the wall, and is there another way?”

而且,如果CBT-I不起作用,亚利桑那大学睡眠和健康研究计划的主任迈克尔·格兰德纳(Michael Grandner)在2024年睡眠:接受和承诺疗法或采取行动中提出了替代方案。基本思想正是名字所暗示的。你接受你的东西。您什么都不改变。如果您无法入睡,或者您无法入睡,或者您只能在断线中睡觉,这是我无法控制的事情之一。(人们可以看到这种咒语可能会对一个人的睡眠有何帮助。)然后,您隔离了对您重要的事情。第二天起作用?做好父母?好朋友?如果睡眠是隐喻的墙,您会不断地撞到头,“您的问题是墙吗?”格兰德纳问。“还是您无法超越墙壁的问题,还有另一种方法吗?”

Because there often is another way. To be a good friend, to be a good parent, to be who and whatever it is you most value—you can live out a lot of those values without adequate sleep. “When you look at some of these things,” Grandner said, “what you find is that the pain”—of not sleeping—“is actually only a small part of what is getting in the way of your life. It’s really less about the pain itself and more about the suffering around the pain, and that’s what we can fix.”

因为经常有另一种方式。成为一个好朋友,成为一个好父母,成为您最有价值的人,无论是谁,您都可以在没有足够睡眠的情况下实现很多这些价值。格兰德纳说:“当您看一些这些事情时,您发现的是痛苦”(不睡觉),“实际上只是您一生中所获得的一小部分。实际上,痛苦本身和痛苦痛苦的痛苦实际上是痛苦,这就是我们可以解决的。”

Even as I type, I’m skeptical of this method too. My insomnia was so extreme at 29, and still can be to this day, that I’m not sure I am tough enough—or can summon enough of my inner Buddha (barely locatable on the best of days)—to transcend its pain, at once towering and a bore. But if ACT doesn’t work, and if CBT-I doesn’t work, and if mindfully meditating and acupuncture and neurofeedback and the zillions of other things I’ve tried in the past don’t work on their own … well … I’ll go back on medication.

即使我键入,我也对此方法表示怀疑。我的失眠是如此极端,在29岁时,至今仍然可以是,以至于我不确定自己足够坚强 - 或者能够召唤出足够多的内在佛(在最好的日子里几乎是可以找到的) - 一次超越痛苦,立刻高耸和钻孔。但是,如果ACT不起作用,并且CBT-I不起作用,并且如果仔细冥想,针灸和神经反馈以及我过去尝试过的其他事物都无法自行起作用……好吧……我会重新使用药物。

Some people will judge me, I’m sure. What can I say? It’s my life, not theirs.

我敢肯定,有些人会评判我。我能说什么?这是我的生活,而不是他们的生活。

I’ll wrap up by talking about an extraordinary man named Thomas Wehr, once the chief of clinical psychobiology at the National Institute of Mental Health, now 83, still doing research. He was by far the most philosophical expert I spoke with, quick to find (and mull) the underlayer of whatever he was exploring. I really liked what he had to say about sleep.

我将讨论一个名叫托马斯·韦尔(Thomas Wehr)的非凡人物,曾经是国家心理健康研究所的临床心理生物学主管,现年83岁,仍在进行研究。到目前为止,他是我与之交谈的最哲学专家,很快找到(并仔细地)是他正在探索的任何东西。我真的很喜欢他对睡眠的看法。

You’ve probably read the theory somewhere—it’s a media chestnut—that human beings aren’t necessarily meant to sleep in one long stretch but rather in two shorter ones, with a dreamy, middle-of-the-night entr’acte. In a famous 2001 paper, the historian A. Roger Ekirch showed that people in the pre-electrified British Isles used that interregnum to read, chat, poke the fire, pray, have sex. But it was Wehr who, nearly 10 years earlier, found a biological basis for these rhythms of social life, discovering segmented sleep patterns in an experiment that exposed its participants to 14 hours of darkness each night. Their sleep split in two.

您可能已经在某个地方阅读了该理论(它是媒体栗子),即人类不一定意味着要在一个漫长的时间内睡觉,而是在两个较短的室内,有一个梦幻般的中间,晚上。历史学家A. Roger Ekirch在2001年著名的2001年报纸中表明,前电之前的不列颠群岛的人们使用Interregnum来阅读,聊天,戳火,祈祷,做爱。但是,近10年前的是Wehr为这些社交生活节奏找到了一个生物学基础,在一次实验中发现了分段的睡眠模式,该实验每晚将参与者暴露于14小时的黑暗中。他们的睡眠分为一分。

Wehr now knows firsthand what it is to sleep a divided sleep. “I think what happens as you get older,” he told me last summer, “is that this natural pattern of human sleep starts intruding back into the world in which it’s not welcome—the world we’ve created with artificial light.”

Wehr现在要亲身知道睡眠的睡眠是什么。去年夏天,他告诉我,“我认为随着年龄的增长会发生什么,这是人类睡眠的这种自然模式开始侵入不受欢迎的世界 - 我们用人造光创造的世界。”

There’s a melancholy quality to this observation, I know. But also a beauty: Consciously or not, Wehr is reframing old age as a time of reintegration, not disintegration, a time when our natural bias for segmented sleep reasserts itself as our lives are winding down.

我知道,这种观察的素质具有忧郁的品质。但也是一种美丽:有意识地,Wehr正在将年龄重新定义为重新融入的时代,而不是解体,这是我们自然的偏见,因为我们的生活逐渐消失,我们对分割的睡眠的自然偏见会重新确定自己。

His findings should actually be reassuring to everyone. People of all ages pop awake in the middle of the night and have trouble going back to sleep. One associates this phenomenon with anxiety if it happens in younger people, and no doubt that’s frequently the cause. But it also rhymes with what may be a natural pattern. Perhaps we’re meant to wake up. Perhaps broken sleep doesn’t mean our sleep is broken, because another sleep awaits.

他的发现实际上应该让所有人放心。各个年龄段的人都在半夜醒着,很难回去睡觉。如果在年轻人中发生这种现象,这一现象将与焦虑联系起来,毫无疑问,这常常是原因。但这也押韵可能是一种自然模式。也许我们打算醒来。也许睡眠不足并不意味着我们的睡眠会破裂,因为另一个睡眠正在等待。

And if we think of those middle-of-the-night awakenings as meant to be, Wehr told me, perhaps we should use them differently, as some of our forebears did when they’d wake up in the night bathed in prolactin, a hormone that kept them relaxed and serene. “They were kind of in an altered state, maybe a third state of consciousness you usually don’t experience in modern life, unless you’re a meditator. And they would contemplate their dreams.”

韦尔告诉我,如果我们想到那些中晚上的觉醒,也许我们应该以不同的方式使用它们,就像我们的一些前辈在夜晚醒来时所做的那样,一种激素,一种使它们放松和宁静的激素。“他们处于一种改变状态,也许是您通常在现代生活中不经历的第三种意识状态,除非您是冥想者。他们会考虑自己的梦想。”

Night awakenings, he went on to explain, tend to happen as we’re exiting a REM cycle, when our dreams are most intense. “We’re not having an experience that a lot of our ancestors had of waking up and maybe processing, or musing, or let’s even say ‘being informed’ by dreams.”

他继续解释了夜间觉醒,当我们离开一个梦想最激烈的时候,我们往往会发生REM周期。“我们没有经验,许多祖先都有醒来,也许正在加工或沉思,或者让我们甚至说“被告知”的经验。”

We should reclaim those moments at 3 or 4 a.m., was his view. Why not luxuriate in our dreams? “If you know you’re going to fall back asleep,” he said, “and if you just relax and maybe think about your dreams, that helps a lot.”

我们应该在凌晨3点或4点回收那些时刻。为什么不在我们的梦中奢侈呢?他说:“如果您知道自己会睡着了,如果您只是放松身心并可能考虑自己的梦想,那就有所帮助。”

This assumes one has pleasant or emotionally neutral dreams, of course. But I take his point. He was possibly explaining, unwittingly, something about his own associative habits of mind—that maybe his daytime thinking is informed by the meandering stories he tells himself while he sleeps.

当然,这是假设一个人有愉快或情感中立的梦想。但是我说他的观点。他可能在不知不觉地解释了自己的社会思想习惯 - 也许他的白天思考是他在睡觉时告诉自己的曲折故事所告知的。

The problem, unfortunately, is that the world isn’t structured to accommodate a second sleep or a day informed by dreams. We live unnatural, anxious lives. Every morning, we turn on our lights, switch on our computers, grab our phones; the whir begins. For now, this strange way of being is exclusively on us to adapt to. Sleep doesn’t much curve to it, nor it to sleep. For those who struggle each night (or day), praying for what should be their biologically given reprieve from the chaos, the world has proved an even harsher place.

不幸的是,问题是,世界没有结构旨在容纳第二次睡眠或梦dream以求的一天。我们过着不自然的,焦虑的生活。每天早晨,我们打开灯光,打开计算机,抓住手机;呼啸开始。就目前而言,这种奇怪的存在方式仅在我们身上适应。睡眠不多,也不会睡觉。对于那些每天晚上(或白天)挣扎的人,为自己的生物学上的祈祷而祈祷,这是一个更加苛刻的地方。

But there are ways to improve it. Through policy, by refraining from judgment—of others, but also of ourselves. Meanwhile, I take comfort in the two hunter-gatherer tribes Wehr told me about, ones he modestly noted did not confirm his hypothesis of biphasic sleep. He couldn’t remember their names, but I later looked them up: the San in Namibia and the Tsimané in Bolivia. They average less than 6.5 hours of sleep a night. And neither has a word for insomnia.

但是有一些方法可以改善它。通过政策,避免判断他人的判断,但也是我们自己。同时,我在两个狩猎采集者部落中感到安慰,Wehr告诉我,他谦虚地指出,他没有确认他对双相睡眠的假设。他不记得他们的名字,但后来我查找了他们:纳米比亚的圣和玻利维亚的Tsimané。他们平均每晚睡眠不到6.5小时。而且都没有失眠的一句话。