In the summer of 2008, I was 19 years old, halfway through college, and an aspiring poet with a notebook full of earnest stanzas of questionable quality. I loved writing. I loved literature. As I considered what sort of career might suit me, I became curious about the life of a book editor. So I made my way to New York City for an internship I had received at a major publishing house. Joining me were four other interns—two Black women and two Asian women. The idea was to open industry doors to students from backgrounds underrepresented in the field.

在2008年夏天,我19岁,上大学的一半,还有一位有抱负的诗人,笔记本上充满了质量可疑的节。我喜欢写作。我喜欢文学。当我考虑过什么样的职业可能适合我时,我对书籍编辑的生活感到好奇。因此,我前往纽约市,在一家大型出版社接受了实习。加入我的还有另外四个实习生 - 两名黑人妇女和两名亚洲妇女。这个想法是要向该领域中代表不足的背景的学生打开行业大门。

I felt primed for the experience, fresh from a transformative college course that introduced me to the history of Black American letters, anchored by The Norton Anthology of African American Literature. Published in 1996 by W. W. Norton and edited by the scholars Henry Louis Gates Jr. and Nellie Y. McKay, the book traversed three centuries of writing, from the Negro spirituals of the 18th century to the poetry and prose of the late 20th century. This was the volume, many said, that had assembled and indexed a Black American literary canon for the first time. Toward the anthology’s close, I found myself spellbound by Toni Morrison’s 1973 novel, Sula, and intrigued by a single line in her biography: Not long after she published her first novel, “Morrison became a senior editor at Random House.”

我为这次经历而感到精彩,这是一个变革性的大学课程,这使我介绍了由非裔美国人文学的诺顿选集锚定的黑人美国信件的历史。W. W. Norton于1996年出版,由学者亨利·路易斯·盖茨(Henry Louis Gates Jr.)和内莉·麦凯(Nellie Y.许多人说,这是第一次组装和索引的卷。走向选集《结束》,我发现自己被托尼·莫里森(Toni Morrison)的1973年小说《苏拉》(Sula)迷住了,并在她的传记中被一条线上的一行着迷:不久之后,她出版了她的第一本小说《莫里森成为兰德之家的高级编辑》。

I’d never known that Morrison had straddled the line between writer and editor. Perhaps naively, I hadn’t envisioned that someone could do both jobs at once, especially a writer of Morrison’s caliber. And I didn’t know then how many of the writers who surrounded her in the Norton volume—Lucille Clifton, June Jordan, Leon Forrest, Toni Cade Bambara—as well as figures beyond the anthology, such as Angela Davis, Muhammad Ali, and Huey P. Newton, had relied on Morrison to usher their books into the world. I certainly did not appreciate how dynamic—and complicated—both the art and the business of those collaborations had been for her.

我从来不知道莫里森跨越了作家和编辑之间的界限。也许天真的,我没有想象有人可以立即做这两个工作,尤其是莫里森的才能的作家。那时,我不知道有多少人在诺顿卷中包围她的作家 - 卢西尔·克利夫顿,六月·乔丹,莱昂·福雷斯特,托尼·卡德·班巴拉(Toni Cade Bambara),以及除了选集之外的数字,例如安吉拉·戴维斯(Angela Davis),穆罕默德·阿里(Muhammad Ali),穆罕默德·阿里(Muhammad Ali)和休伊·P·牛顿(Huey P.我当然不欣赏这些合作的艺术和业务对她的动态和复杂性。

Now readers can discover Morrison the bold and dogged editor, thanks to a deeply researched and illuminating new book, Toni at Random: The Iconic Writer’s Legendary Editorship, by Dana A. Williams, a scholar of African American literature and the dean of Howard University Graduate School. Decades of path-clearing and advocacy had preceded the Norton anthology, and Morrison, as the first Black woman to hold a senior editor position at the prominent publishing house, had played a major part. In a 2022 interview, Gates remarked that Random House’s hiring of Morrison, at the height of the civil-rights movement, was “probably the single most important moment in the transformation of the relationship of Black writers to white publishers.”

现在,读者可以发现莫里森(Morrison)是一位大胆而顽强的编辑,这要归功于一本深入研究和启发的新书《随机:标志性作家的传奇编辑》(The Toni:Toni),由非裔美国人文学学者和霍华德大学研究生院院长达娜·威廉姆斯(Dana A. Williams)撰写。数十年来的通道清理和倡导曾是诺顿选集之前的,而莫里森(Morrison)是第一位在著名出版社担任高级编辑职位的黑人妇女,扮演了重要角色。在2022年的一次采访中,盖茨指出,兰登书屋(Random House)在民权运动高峰期雇用莫里森(Morrison)是“可能是黑人作家与白人出版商之间关系转变的最重要时刻。”

A pronouncement like that runs the risk of hyperbole, but Williams’s meticulous and intimate account of Morrison’s editorial tenure backs up the rhetoric. How Morrison handled the pressures of wielding her one-of-a-kind influence is fascinating—and, in retrospect, telling: As an editor, she was not just tenacious, but also always aware of how tenuous progress in the field could be. And it still can be: The recent departures of prominent Black editors and executives who helped diversify publishing’s ranks after George Floyd’s murder in 2020 are a stark reminder of that.

像这样的声明具有夸张的风险,但威廉姆斯对莫里森的社论任期的细致而亲密的说法却恢复了言论。莫里森如何处理挥舞自己独一无二的影响力的压力令人着迷 - 回想起来,他说:作为一名编辑,她不仅是顽强的,而且总是意识到该领域的进步可能是多么艰难。仍然可以是:杰出的黑人编辑和高管的最近出发,他们在乔治·弗洛伊德(George Floyd)在2020年被谋杀后帮助多样化了出版的行列,这使人们想起了这一点。

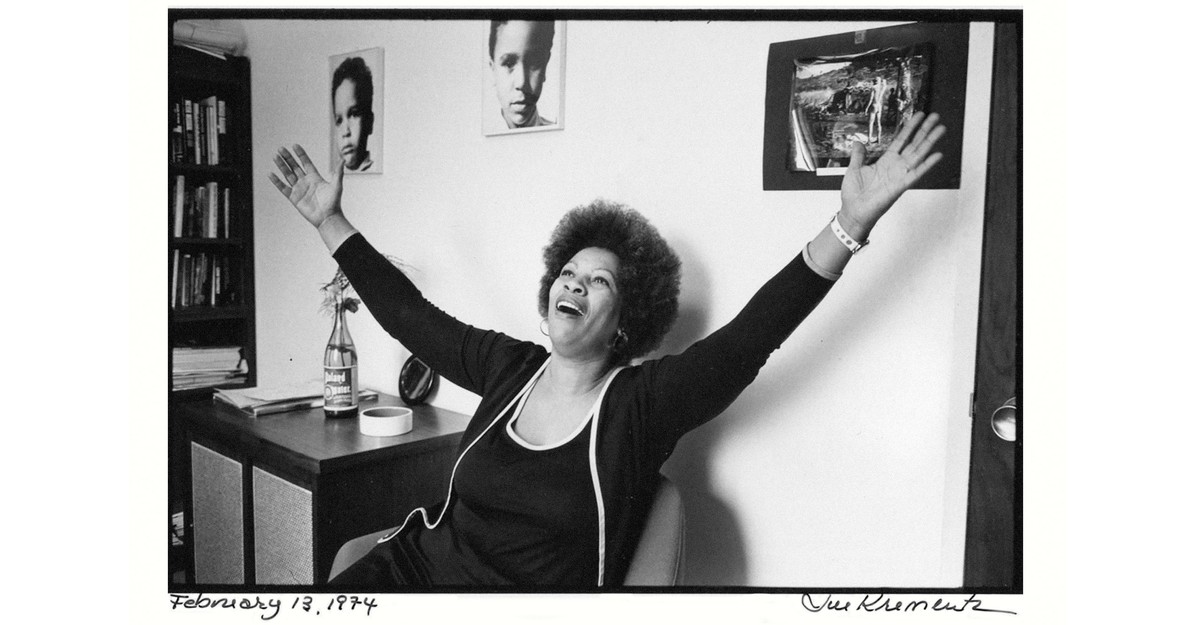

Morrison and her colleague Errol McDonald at Random House (Jill Krementz)

莫里森(Morrison)和她的同事Errol McDonald在Random House(Jill Krementz)

Morrison’s arrival at Random House in the late 1960s, a fraught and fertile moment, was well timed, though her route there wasn’t direct. She was born Chloe Ardelia Wofford in 1931 in the midwestern steel town of Lorain, Ohio, to parents who, like so many millions of Black Americans in that era, had fled the racial violence of the South in search of safety and economic opportunities farther north. They recognized their daughter’s brilliance early (as did teachers) and began scraping together money to make college possible. Morrison went to Howard, majoring in English, minoring in classics, and throwing herself into theater. After getting a master’s degree in American literature from Cornell University and teaching at Texas Southern University, she went back to Howard in 1957 and spent seven years in the English department. She joined a writing group, whose members loved some pages she shared about a young Black girl who wishes her eyes were blue—the seeds of her debut novel, The Bluest Eye.

莫里森(Morrison)在1960年代后期到达兰登书屋(Random House),这是一个充满活力和肥沃的时刻,尽管她的路线没有直接。她于1931年在中西部钢铁镇洛林(Lorain)出生,俄亥俄州洛兰(Lorain),父母像那个时代的数百万美国人一样,他们逃离了南方的种族暴力,以寻找安全和经济机会。他们很早就意识到女儿的才华(老师也是如此),并开始刮一起钱以使大学成为可能。莫里森(Morrison)去了霍华德(Howard),主修英语,在经典赛上矿区,然后将自己扔进剧院。在从康奈尔大学获得美国文学硕士学位并在德克萨斯州南部大学任教后,她于1957年回到霍华德,并在英语系工作了七年。她加入了一个写作小组,他们的成员喜欢她分享的一些关于一个年轻的黑人女孩,她希望自己的眼睛是蓝色的,这是她处女作小说《最蓝眼睛》的种子。

Morrison also married, had a child, and divorced, before returning home to Ohio in 1964, pregnant and in search of a new start. One day not long after, three copies of the same issue of The New York Review of Books were accidentally delivered, carrying an ad for an executive-editor job at a small textbook publisher in Syracuse that had recently been acquired by Random House. Morrison’s mother said the mistake was a sign that she should apply. Morrison’s first novel was still several years off, and she needed a steady job that would allow her to focus on her writing in the evenings. She was hired and spent a few years at the publisher before it was fully absorbed by Random House, one of whose top executives had been struck by her intellect and editorial adroitness. She was soon offered a job as an editor on the trade, or general interest, side. She accepted.

莫里森(Morrison)也结婚了,育有一个孩子并离婚,然后于1964年回到俄亥俄州,怀孕并寻找新的起点。不久之后,纽约书籍评论的三本副本被意外交付,在锡拉丘兹的一家小型教科书出版商处携带了一份广告,该广告最近被兰登书屋收购。莫里森的母亲说,这个错误是她应该申请的标志。莫里森(Morrison)的第一本小说仍然有几年的时间,她需要一份稳定的工作,这将使她能够在晚上专注于写作。在出版商被兰登书屋(Random House)完全吸收之前,她被雇用并在出版商中度过了几年,他们的一位高管被她的智力和社论忠实者震惊。很快,她就可以担任交易或一般利益的编辑。她接受了。

Amid racial upheaval and widespread student protests, Black studies and African studies were on the rise, transforming how the history, literature, and culture of the Black diaspora were taught. “I thought it was important for people to be in the streets,” Morrison later said. “But that couldn’t last. You needed a record. It would be my job to publish the voices, the books, the ideas of African Americans. And that would last.”

在种族动荡和广泛的学生抗议活动中,黑人研究和非洲研究正在上升,改变了黑人侨民的历史,文学和文化。莫里森后来说:“我认为人们在街上很重要。”“但这不能持续。您需要唱片。发表声音,书籍,非裔美国人的思想是我的工作。这将持续下去。”

Read: Has the DEI backlash come for publishing?

阅读:Dei强烈反弹来出版了吗?

Her galvanizing insight as an editor was that “a good writer,” as Williams puts it, “could show the foolishness of racism,” as well as the many facets of Black life, “without talking to or about white people at all.” Morrison came to appreciate the power of directly exploring the inner and outer dimensions of Black life as she edited two groundbreaking anthologies: one that brought together some of the best African fiction writers, poets, and essayists, Contemporary African Literature, and another called The Black Book, which documented Black American history and daily experience through archival documents, cultural artifacts, and photographs. A frustration with the focus she found in the work of some homegrown Black writers also shaped her thinking. As she said later,

正如威廉姆斯(Williams)所说的那样,她作为编辑的宣传见解是,“一位好作家”,“可以表现出种族主义的愚蠢”,以及黑人生活的许多方面,“根本不谈论白人或谈论白人。”莫里森(Morrison)欣赏了直接探索黑人生活的内在和外部维度的力量,因为她编辑了两种突破性的选集:一部将一些非洲小说作家,诗人和散文家,当代非洲文学和另一本名为“黑书”的最佳非洲小说作家汇集在一起,该书记录了黑人黑人的历史和日常经验,并通过档案文献,文化文化,文化,图片和照片,以及照片,和照片。她在一些本土黑人作家的作品中发现的重点感到沮丧,也塑造了她的思想。正如她稍后说的那样

I realized that with all the books I’d read by contemporary Black American writers—men that I admired, or was sometimes disturbed by—I felt they were not talking to me. I was sort of eavesdropping as they talked over my shoulder to the real (white) reader. Take Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man: That title alone got me. Invisible to whom?

我意识到,当我欣赏或有时被当代黑人美国作家读过的所有书籍,我觉得他们没有和我说话。当他们在我的肩膀上和真实的(白色)读者的肩膀上说话时,我有点窃听。以拉尔夫·埃里森(Ralph Ellison)的隐形男人:仅这个头衔就让我得到了我。对谁看不见?

Morrison recognized, Williams writes, that this “editorial aesthetic” of hers made her work harder. Famous for giving its editors unusual freedom, Random House was all for unearthing new writers and creating a new readership. Still, reaching a general audience remained a trade publisher’s mandate. A salesman at a conference once told Morrison, “We can’t sell books on both sides of the street”: There was an audience of white readers and, maybe, an audience of Black readers, he meant, but those literary worlds didn’t merge. “Well, I’ll just solve that,” Morrison decided. She was determined to “do something that everybody loves” without losing sight of her commitment to Black readers.

威廉姆斯写道,莫里森认识到,这种“社论美学”使她的工作变得更加努力。兰登书屋(Random House)以赋予其异常自由的编辑而闻名,全都是出土新作家并创造新的读者。尽管如此,吸引普通观众仍然是贸易出版商的任务。一次会议上的推销员曾经告诉莫里森:“我们不能在街道两边卖书”:有白人读者的观众,也许是黑人读者的观众,但他的意思是,但是那些文学世界并没有合并。“好吧,我会解决这个问题,”莫里森决定。她决心“做每个人都喜欢的事情”,而又不会失去对黑人读者的承诺。

To pull off that feat, Morrison’s mode was to be relentlessly demanding—of herself, her authors, and her Random House colleagues. She tailored her rigorous style to the varied array of Black writers she didn’t hesitate to pitch to her bosses. But whether she was editing her high-profile nonfiction authors—Newton, the Black Panther leader, and others—or largely unknown and highly unconventional fiction writers, among them Gayl Jones, her protective impulse stands out.

为了实现这一壮举,莫里森的模式将不懈地要求 - 她自己,作者和她的兰登书屋同事。她为自己的严格风格量身定制了各种各样的黑人作家,她毫不犹豫地向老板们投球。但是,无论她是在编辑她的备受瞩目的非小说作家 - 纽顿,黑豹领袖和其他人,还是很大程度上不明的和非常规的小说作家,其中包括盖尔·琼斯(Gayl Jones),她的保护性冲动都脱颖而出。

Angela Davis and Toni Morrison in New York City (Jill Krementz)

纽约市的安吉拉·戴维斯(Angela Davis)和托尼·莫里森(Toni Morrison)

As they worked on their books with Morrison, Newton as well as the activist Davis resisted the pressure to lean into the sort of personal reflections the public was curious about, and she supported them, while insisting that their thinking be clearly laid out. For Newton’s 1972 collection of writings, To Die for the People, that meant tossing weak early essays and reediting the rest, even those that had already been published. But her aim was not to present his ideas “all smoothed out,” Williams writes. Morrison emphasized that “contradictions are useful” in accurately tracing the evolution of the Black Panther Party away from a focus on armed revolution and toward the goal of creating social infrastructure within communities, offering programs such as free breakfast for students. She felt that a reflective Newton should emerge from the book’s pages. Aware of the public narrative that positioned the Panthers as unhinged, violent racial nationalists, Morrison encouraged him to describe “what he believes are errors in judgment in the Party line behavior.”

当他们与莫里森(Morrison)以及牛顿(Newton)以及激进主义者戴维斯(Davis)一起工作时,戴维斯(Davis)抵制了倾向于公众感到好奇的个人思考的压力,她支持他们,同时坚持认为他们的思想明确布置了。为了使牛顿1972年的著作收藏,为人民而死,这意味着要抛弃薄弱的早期论文并重新编辑其余的文章,即使是已经出版的人也是如此。威廉姆斯写道,她的目的不是要提出他的想法“一切顺利”。莫里森(Morrison)强调,“矛盾是有用的”,可用于准确追踪黑豹党的演变,从武装革命的关注到在社区内建立社会基础设施的目标,为学生提供免费早餐等计划。她认为牛顿应该从书的页面中浮现出反思性的牛顿。莫里森(Morrison)意识到将黑豹(Panthers)定位为无林,暴力的种族民族主义者的公共叙述,他鼓励他描述“他认为这是党派行为中的审判错误”。

She worked more intimately with Davis, whom she sought out right after Davis’s acquittal on charges of murder, kidnapping, and criminal conspiracy (resulting from a courthouse raid in which guns that were registered to Davis were used). For a time, Davis even moved in with Morrison and her two sons, then living in Spring Valley, New York. As they progressed through what became Angela Davis: An Autobiography (1974), their friendship seems to have made Morrison fiercer in deflecting calls for more personal revelation (which she considered sexist code for sensational romantic-life details). She bridled at one reader’s report asking for, among other things, more signs of Davis’s “humanness” in the draft. In a memo to Random House’s editor in chief, Morrison remarked that humanness is “a word white people use when they want to alter an ‘uppity’ or ‘fearless’ ” Black person.

她与戴维斯(Davis)合作更加亲密,戴维斯(Davis)在戴维斯(Davis)无罪犯罪,罪名是谋杀,绑架和犯罪阴谋(是由一场法院袭击造成的,该突袭造成了向戴维斯注册的枪支的袭击)。一段时间以来,戴维斯甚至与莫里森和她的两个儿子一起搬进去,然后住在纽约的斯普林谷。当他们通过成为安吉拉·戴维斯(Angela Davis)的东西:自传(1974年)时,他们的友谊似乎使莫里森(Morrison)变得更加激烈地偏离了更多个人启示的呼吁(她认为这是轰动性浪漫生活细节的性别歧视法)。她在一位读者的报告中援引了戴维斯在草案中的“人性”的更多迹象。莫里森(Morrison)在《兰登书屋(Random House)》(Random House)的主编的备忘录中说,人类是“白人想改变“ upperity”或“无所畏惧”的黑人时,人类是一个单词。

At the same time, she pushed Davis for more vivid storytelling, and less academic vagueness in her account of her political life, her time in prison, her trial. At one point, Morrison chided her that “humanity is a vague word in this context,” evidently referring to Davis’s discussion of incarceration:

同时,她推动了戴维斯(Davis)进行更加生动的讲故事,并且在她的政治生活,监狱和审判的情况下,较少的学术模糊性。有一次,莫里森(Morrison)认为“在这种情况下人类是一个模糊的词”,显然是指戴维斯(Davis)对监禁的讨论:

You repeat the idea frequently throughout so it is pivotal. “Breaking will” is clear; forcing prisoners into childlike obedience is also clear; but what is erode their humanity. Their humaneness? Their natural resistance?

您在整个过程中经常重复这个想法,因此它是关键的。“破坏意志”很明显;强迫囚犯进入幼稚的服从也很清楚。但是什么侵蚀了他们的人性。他们的人性?他们的自然抵抗?

Morrison bore down on publicity for the book too, famous though its author already was. She secured a blurb from the well-known British leftist Jessica Mitford, who wrote about prison reform too. Still, Morrison’s commitment to Black readership was unrelenting, and Random House arranged to provide hosts of book parties for Davis in Black communities with copies at a 40 percent discount. The party conveners could sell them at regular price and keep the profit.

莫里森(Morrison)也为这本书宣传,尽管作者已经很有名。她从著名的英国左派杰西卡·米特福德(Jessica Mitford)那里获得了宣传,后者也写了有关监狱改革的文章。尽管如此,莫里森对黑人读者的承诺仍然不懈,兰登书屋(Random House)安排为戴维斯(Davis)在黑人社区提供副本的主持人,副本以40%的折扣。聚会召集人可以以常规价格出售并保持利润。

Morrison in 1978 (Jill Krementz)

莫里森(Morrison)在1978年(吉尔·克雷兹兹(Jill Krezmentz))

Always on the lookout for new talent, Morrison asked friends who taught in creative-writing departments to send promising work by their students her way. In 1973, she dug into a box of manuscripts sent by the poet Michael Harper at Brown University. The writer was Gayl Jones, then in her early 20s, and Morrison was stunned by her narratively experimental prose. “This girl,” she felt, “had changed the terms, the definitions of the whole enterprise” of novel writing. Morrison, confessing that she was “green with envy,” immediately set up a meeting with Jones and soon persuaded the higher-ups at Random House to give her a book deal. She and Jones turned first to the draft of a novel titled Corregidora, which tackled the sexual exploitation of women entrapped in slavery, and its psychological and spiritual toll, in a more devastating and effective way than Morrison had ever encountered.

莫里森(Morrison)一直在寻找新的人才,他问在创意写作部门任教的朋友,以他们的学生方式派遣有前途的工作。1973年,她挖掘了布朗大学诗人迈克尔·哈珀(Michael Harper)派遣的一盒手稿。作家是盖尔·琼斯(Gayl Jones),然后是20多岁,莫里森(Morrison)被她的叙事实验性散文震惊。她觉得“这个女孩改变了新写作的术语,整个企业的定义”。莫里森(Morrison)承认,她“嫉妒绿色”,立即与琼斯(Jones)举行了一次会议,并很快说服了兰登书屋(Random House)的高级往返,以给她一笔交易。她和琼斯首先转向了一本名为《科雷格拉(Corregidora)的小说》,该小说以比莫里森(Morrison)遇到的更具毁灭性和有效的方式解决了对奴隶制陷入的妇女的性剥削,其心理和精神损失。

From the September 2020 issue: Calvin Baker on the best American novelist whose name you may not know

从2020年9月的《杂志》中:加尔文·贝克(Calvin Baker)在美国最好的小说家中

Spurred on by her fervent belief in Jones’s talent, Morrison was determined to ensure that Corregidora made an impression, well aware of how a successful debut could define a fiction writer’s career—particularly that of a Black woman fiction writer. She set exacting standards, bluntly calling Jones out when she thought she was taking shortcuts: “For example, Ursa’s song ought to be a straight narrative of childhood sexual fears,” she wrote to Jones, and went on: “May Alice and the boys—the fragments are really a cop out. You know—being too tired or impatient to write it out.” Understanding how shy Jones was, Morrison joined her for interviews and used her own literary capital (Sula had recently appeared to acclaim) to advocate for her work. “No novel about any black woman can ever be the same after this,” Morrison declared in a 1975 article in Mademoiselle.

莫里森(Morrison)坚决对琼斯的才华的信念激发了她的信念,他决心确保科雷格拉(Corregidora)给人留下深刻的印象,非常意识到成功的首次亮相如何定义小说作家的职业,尤其是黑人女性小说作家的职业。她设定了严格的标准,当她认为自己正在捷径时,直言不讳地呼唤出来:“例如,乌尔萨(Ursa)的歌曲应该是对童年性恐惧的直接叙述,”她写信给琼斯(Jones),然后继续说:“愿爱丽丝(May Alice)和男孩们 - 碎片 - 碎片真的很疲倦或烦人,无法疲倦或烦恼。”莫里森(Morrison)了解琼斯(Jones)的身高,莫里森(Morrison)加入了她的采访,并利用自己的文学首都(最近似乎好评了)来倡导她的工作。莫里森(Morrison)在1975年的一篇文章中宣称:“在此之后,没有关于任何黑人妇女的小说都不会一样。”

Two years later, with the publication of Song of Solomon, Morrison also saw how her stature could get in the way. “In terms of new kinds of writing, the marketplace receives only one or two Blacks,” she later lamented in an interview in Essence magazine, wishing that the books she edited and published sold as well as the ones she wrote. In 1978, after the publication of Jones’s second novel, Eva’s Man, and a story collection, White Rat, Morrison’s once-close relationship with her unraveled amid mounting tensions with Jones’s partner; he had begun to represent Jones, and his behavior had become ever more erratic and aggressive.

两年后,随着所罗门之歌的出版,莫里森还看到了她的身材如何阻碍。后来,她在Essence Magazine的一次采访中感叹:“就新的写作而言,市场只收到一两个黑人。”他希望她编辑和出版的书籍以及她写的书籍。1978年,在琼斯的第二本小说《伊娃的男人》和《白鼠》出版之后,莫里森与琼斯的伴侣越来越紧张的紧张关系,莫里森曾经与她的曾经相关关系。他已经开始代表琼斯,他的行为变得更加不稳定和进取。

By then, Morrison had just published a second novel by Leon Forrest, whose debut, There Is a Tree More Ancient Than Eden, had been a daunting, and thrilling, foray into novel-editing for her, back at the start of the decade. Together they had worked on an introductory section, describing the novel’s large cast of characters, not just to help readers but to orient Morrison herself as she went through the whole manuscript—and to get Random House’s editor in chief to offer Forrest a contract. With a foreword by Ralph Ellison (Morrison saw that two pages of comments he’d sent in would serve that purpose well), the novel was hailed for its risk taking and, Williams writes, for dwelling “in Blackness without reducing Blackness to an object of racism.” Though Forrest’s books lost money, Morrison’s support never wavered, and Random House, following her lead, stuck with him.

到那时,莫里森刚刚发表了莱昂·福雷斯特(Leon Forrest)的第二本小说,他的处女作《有一棵比伊甸园更古老的树》(Tree)令人生畏,令人兴奋,在十年初为她涉足小说编辑。他们共同研究了一个入门部分,描述了小说的大量角色,不仅是为了帮助读者,还为了使莫里森本人在整个手稿中进行关注,并让Random House的编辑主要提供Forrest的合同。在拉尔夫·埃里森(Ralph Ellison)的前言中(莫里森(Morrison)看到他发出的两页评论将很好地实现这一目的),这部小说因冒险而受到欢呼,威廉姆斯(Williams)写道,“居住在黑人中,而不将黑人降低到种族主义对象。”尽管福雷斯特(Forrest)的书损失了钱,但莫里森(Morrison)的支持从未动摇,随后的兰登书屋(Random House)跟随她的领导,坚持了他。

After scaling back on editing for a while, Morrison officially left Random House in 1983. She was eager to stop working on her fiction at night and “in the automobile and places like that,” she joked, and also to stop feeling “guilty that I’ve taken some time away from a full-time job.” The hard-driving editorial mission that had defined nearly two decades of Morrison’s life had never been peripheral for her—and hindsight reveals what a versatile catalyst she’d been in American literary culture. Though her departure was a boon for her own writing, it came at a cost. The number of Black authors who were published by Random House nose-dived after she left.

在缩减编辑一段时间后,莫里森(Morrison)于1983年正式离开兰登书屋。艰苦的社论使命定义了近二十年的莫里森一生,从未对她来说是外围的,事后看来,揭示了她从事美国文学文化的多才多艺的催化剂。尽管她的离开是她自己写作的福音,但这是有代价的。她离开后浪漫馆鼻子发表的黑人作家人数。

That probably didn’t come as a big surprise to Morrison. Seven years earlier, speaking at a conference on the past and future of Black writing in the United States, she had a message for the audience of major Black writers and critics: Don’t expect structural racism within and beyond publishing to disappear—but also don’t let that stop you. “I think that the survival of Black publishing, which to me is a sort of way of saying the survival of Black writing, will depend on the same things that the survival of Black anything depends on,” she said, “which is the energies of Black people—sheer energy, inventiveness and innovation, tenacity, the ability to hang on, and a contempt for those huge, monolithic institutions and agencies which do obstruct us. In other words, we must do our work.”

对于莫里森来说,这可能并不令人惊讶。七年前,她在美国的过去和未来的一次会议上发表讲话,她向主要的黑人作家和评论家的观众传达了一条信息:不要指望出版的结构性种族主义消失,但也不要让这阻止您。她说:“我认为黑人出版的生存是一种说出黑人写作的生存的方式,它将取决于黑人生存所取决于的东西,这是黑人的能量,当时的精力,精力,创新性和创新,坚韧,坚韧,坚韧,坚持不懈,能够悬而未决的能力,而持续了一项巨大的言论,我们必须努力做出我们的努力,而我们的工作是我们的其他方法,而我们的动力也是如此,而我们却在我们的其他方面进行了操作。

This article appears in the August 2025 print edition with the headline “How Toni Morrison Changed Publishing.”

本文出现在2025年8月的印刷版中,标题为“托尼·莫里森(Toni Morrison)如何改变出版”。